Oklahoma has been a launch pad for talent for decades, and for good reason. There seems to be something in the state’s red dirt that both conjures and conducts the raw materials for greatness: resilience, ingenuity and the kind of warmth that come from a community that lifts up its own.

If the yet-to-open OKPOP museum reminds us of one good thing, it’s the unsung but steady drumbeat of talented Oklahomans who’ve departed to create waves in other cities. From Kristin Chenoweth to Bill Hader and Sterlin Harjo, Oklahoma has seen some of its biggest talents strike out to claim their stake. And yet, many who leave feel a strong pull back—either to live, produce projects or draw creative inspiration. What do we make of that inclination to return?

There’s something ineffable about Oklahoma, and to understand it is to reconcile tensions. It’s a place that is at once chronically overlooked and yet impossibly full of life; a young state built on bootstrapped reinvention, stolen land and grave atrocity that holds stories older than we can name. To be from here is to inherit a set of qualities that can’t be manufactured: humility, curiosity, the instinct to create something out of nothing and the arrogance to believe that you can. And perhaps most importantly, an imperative to reckon with complexity without rushing to resolve it.

The “Okie spirit,” it seems, is magnetic, keeping people tethered long after they leave to thrive beyond its borders. But what does it mean to be from a place that is constantly trying to reinvent itself? What happens when the reinvention doesn’t match the picture you’d imagined? And why, no matter how far we roam, do so many of us feel the alluring pull of open pastures calling us home?

Some questions don’t have easy answers, but in the year of our OKC Thunder National Champions 2025, Okie excellence is enduring and visible, and that alone is worth a conversation. We asked a few Oklahomans who’ve set out to build their creative practice in other cities how they feel about their home state now; how that connection drives their work; and if they ever feel the pull back. Here’s what they had to say.

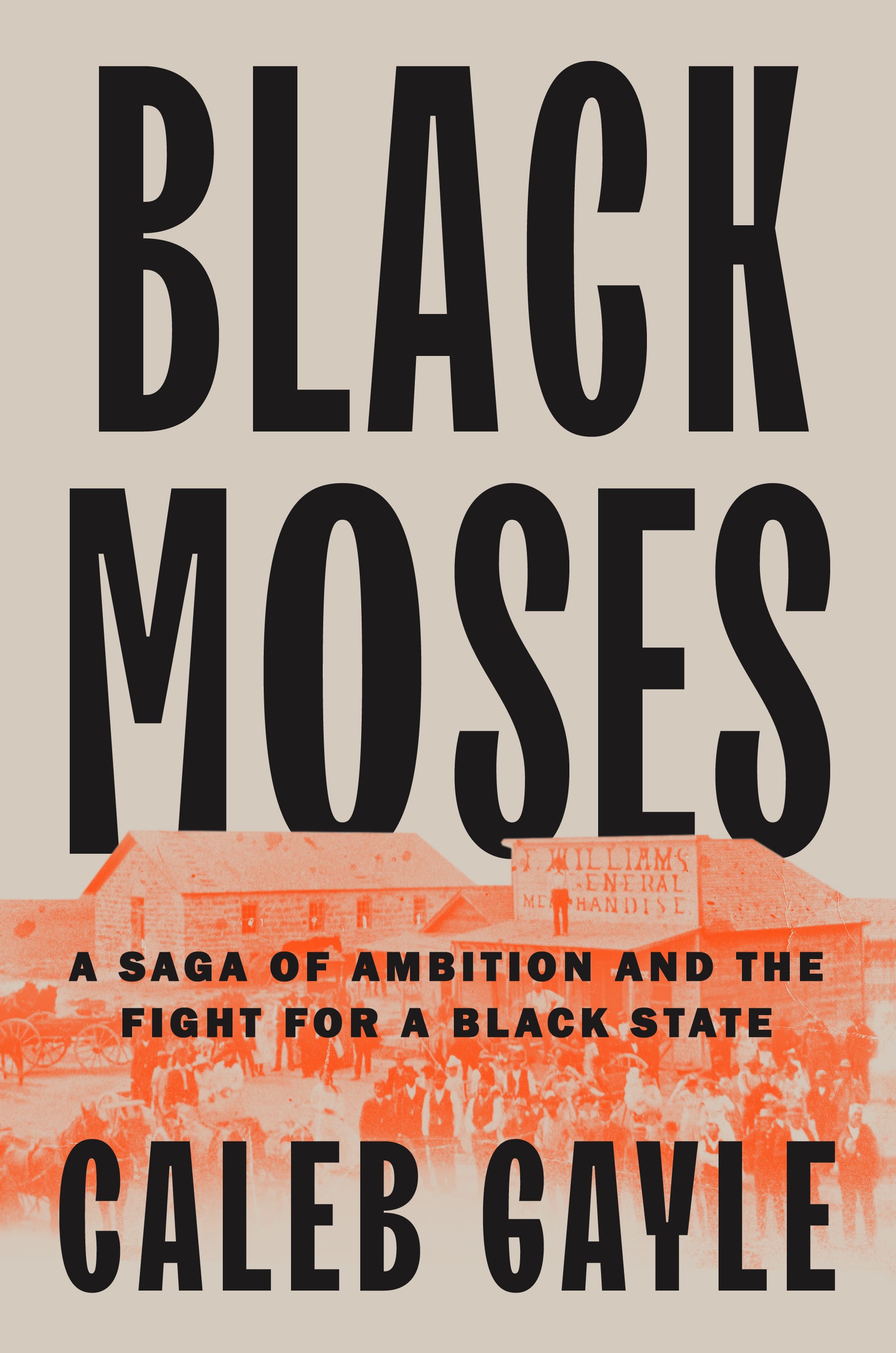

Caleb Gayle: Author, Professor and Writer for The New York Times Magazine, Raised in Tulsa, Lives in Boston

Oklahoma is central to your recent work. Why did you choose to center it creatively?

“Growing up, the goal was to get away from Oklahoma and forget about it. But the reality is that there’s so much about America that I didn’t understand until I returned to the story of Oklahoma. And I think it can help us understand who we are collectively as a country.

“As a writer and historian, the goal is always to help mine that for a reader. Speaking in true market dynamics, it’s fun to give a reader something they otherwise wouldn’t have. There are over 16,000 books about Abraham Lincoln in print currently. But stories like Edward McCabe’s [featured in Gayle’s forthcoming book, Black Moses] are rarely told. So zigging while others zag keeps me more engaged, and helps me understand myself a bit more.

“I also didn’t realize how attracted to ambition I was. The throughline to most of my work is not perfect people living middling lives, but imperfect people trying to live lives greater than they thought possible … I find resonance in subjects that narrate this story with me.”

Do you feel pride about being from Oklahoma?

“There’s just no question that it’s a special place, and there’s a reason why of all the places I’m going to go for this book tour, we’re starting in Oklahoma. It’s not just to see my parents and eat their food, but also because I love the place. And for better and for worse, it raised me.

“I think I have this pride of being part of ‘flyover country’—in part because the term also pisses me off. If I tell someone I’m from Tulsa, there are one or two (probably wildly incorrect) images that probably come to mind, that have nothing to do with our experience of growing up there. Admittedly, being from Oklahoma makes me a far more interesting person than a lot of the people I meet here.”

Do you recognize a sense of pride in other Oklahomans you meet on the coast?

“I think there is this feeling, not that we ‘made it out’—that’s not the testimony we share; it’s more so like that Paul Rudd video on ‘Hot Ones’ where he’s like, ‘Look at us.’ We know what it is to be from the same place … the proximity of our experience develops a certain level of kinship.”

Is there something in Oklahoma’s spirit that makes its people great elsewhere? Or do you have to leave to find greatness?

“I think we are told over and over again that we need to leave in order to achieve something great, which is really sad, and either a reflection of the institution, universities, jobs or what the outlook might be in a place in Oklahoma. We’re preached to that Oklahoma is not a place where you can grow and develop, that you’ve got to leave to achieve anything. And I don’t subscribe to that. I don’t think I needed to leave and go back to be something meaningful.”