Don Thompson was in the right place at a bad time. In the late 1960s, the army veteran was back home in Tulsa the day bulldozers began to tear down the Greenwood section of the city for an incoming highway project.

When Thompson saw what was happening, he hurried home. Not to avoid the destruction that was taking place, but to collect the means to document the events.

The budding photojournalist got out his camera and began chronicling what he could before it was all gone. Those photos became the final images of Black Wall Street before Urban Renewal tore it apart.

“They started tearing down businesses in that area. I thought it was an injustice. And to this day, I still think it was an injustice,” Thompson says. “Bulldozers were going in the area, tearing down businesses. People were losing their homes, their livelihoods. So I wanted to document those areas. And there were very few photographers that I knew of that were in that area. It seemed like I was the only one that was doing this. I felt I had to do this; I think it was my calling. I don’t know why, but I just had to get in there and try to photograph as much as I could.”

The demolition was part of the Federal-Aid Highway Acts of 1965 and 1968, which called for an interstate highway to be built through the Greenwood district. It essentially split Tulsa in two halves, with the predominantly Black and poor on one side and white and economically advantaged on the other.

While a popular narrative is that the Greenwood area and Black Wall Street came to an end during the violence of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, the reality is that Greenwood rebuilt itself and had once again transformed a thriving, self-contained economy.

But according to Thompson, it was half a century later that the district was officially wiped off the map and almost out of the history books with the Inner-Dispersal Loop, which was completed in 1971.

In 2021, President Joe Biden said as much in a proclamation that acknowledged the federal government’s role in Greenwood’s demise. The proclamation was posted on the official White House website. But it has since been removed under President Donald Trump’s administration and replaced with the ubiquitous “404 Page Not Found.”

“I had worked in Greenwood back in the ’60s when I got out of the Army. And I saw the vibrancy, the entrepreneurial spirit of people working in that area. It was a great experience for me,” Thompson recalls. “As a young man, I was really impressed by what I was seeing. You didn’t have to leave the community to find anything, it was right there in that community. Then, in the 1970s, things changed. Eminent domain took over. Redlining of the Greenwood district took place. Urban renewal came in. The bulldozers came in.”

The images Thompson took that day are now part of the permanent collection at the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American Culture and History in Washington, D.C.

However, Thompson never intended to become a photojournalist or community activist. When he first entered the military in the 1960s, he had never taken a photo or even held a camera.

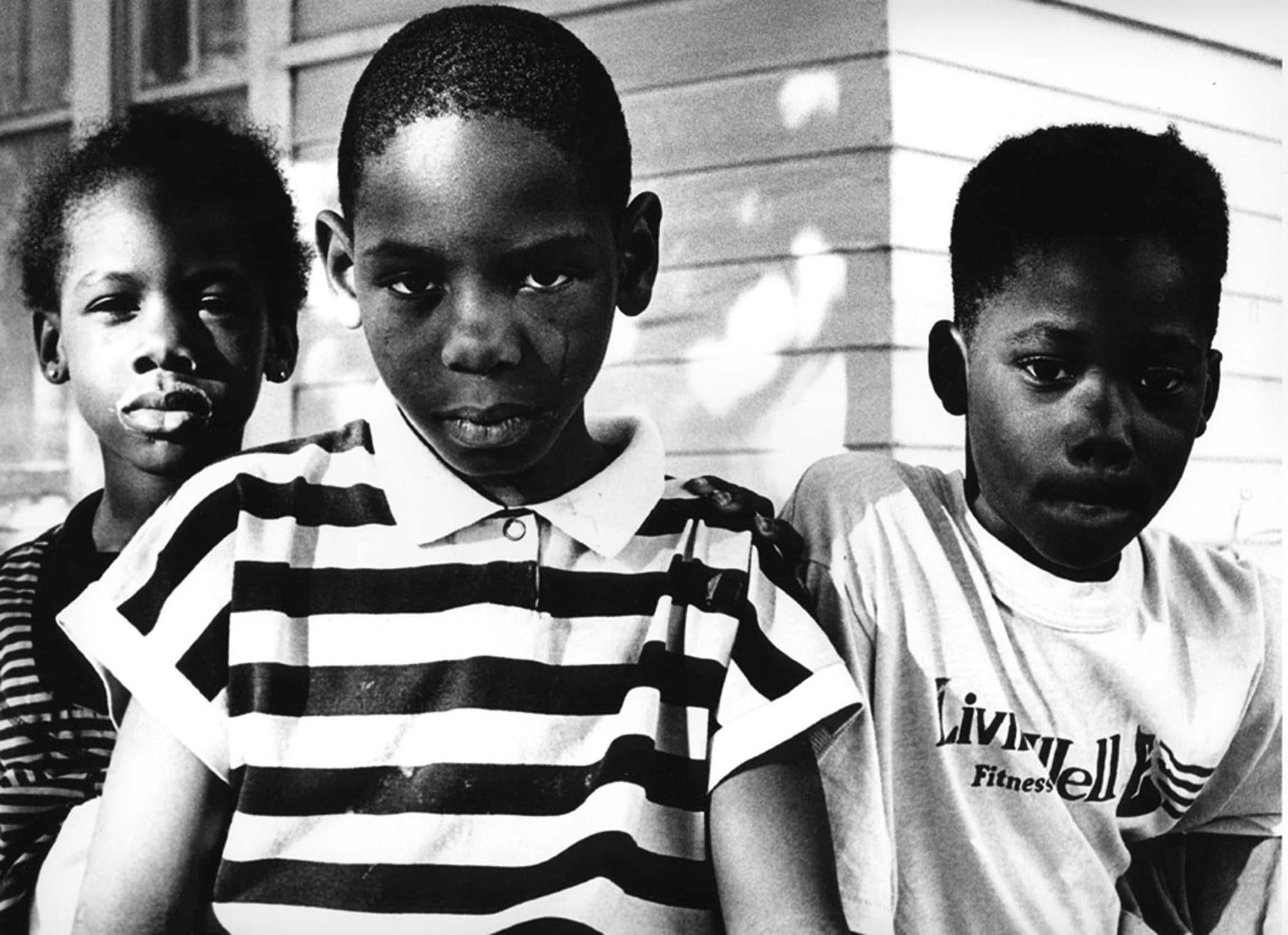

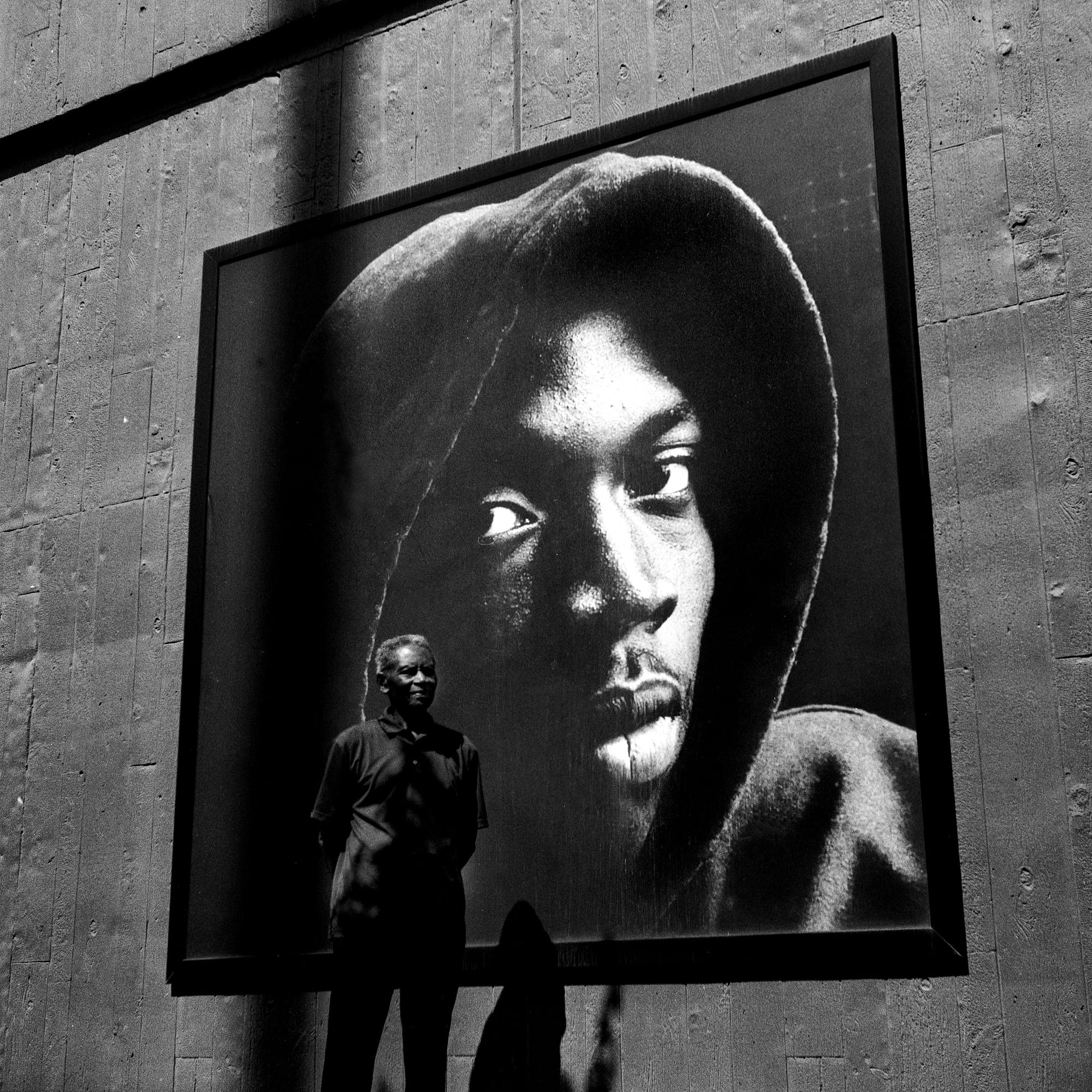

LEFT: “Main Street Kids,” Tulsa, 1991 By Don Thompson - Photo by ©Don Thompson, Courtesy The Hulett Collection. RIGHT: Thompson stands in front of his image “Endangered Species” (1991) along Greenwood’s Pathway of Hope - Photo by Michael Kinney

But once again, he found himself in the right place when fate came knocking: Stationed in Würzburg, Germany, he was working as a public information specialist and wrote articles for newspapers back home.

“One day, the commanding officer called me into his office. He said, ‘Don, you're going to have to take a photograph of our Commanding General,’” Thompson recalled. “He is coming to our company unit, and he’s going to be inspecting our unit. We need you to take photographs.’ I had no camera. I didn’t even know how to take photographs. I didn’t even know what a camera looked like. But I was a 21-year-old kid, and the commanding officer said, ‘You’re going to have to take photographs.”

Thompson went into town, found a camera store and asked the owner what he should get. After he explained his situation, the owner suggested a Yashica Twin Lens Reflex camera and showed Thompson how to operate it.

“I wanted to get into something that I had been really interested in, doing some photographs that Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks and other photographers were doing. I felt that I had a calling on my life to document injustice.” –Don Thompson

“The next day, I went to this area where Earle Wheeler (Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), who was the general of the Army at the time, was going to be,” he says. “I started taking photographs with this twin lens camera. It only held 12 exposures at that time. So I took the photographs, and I prayed to God. I said, ‘I hope this goes well.’”

When Thompson had the film developed, only one photo came out “OK.” He took it to his commanding officer, and was told it would do.

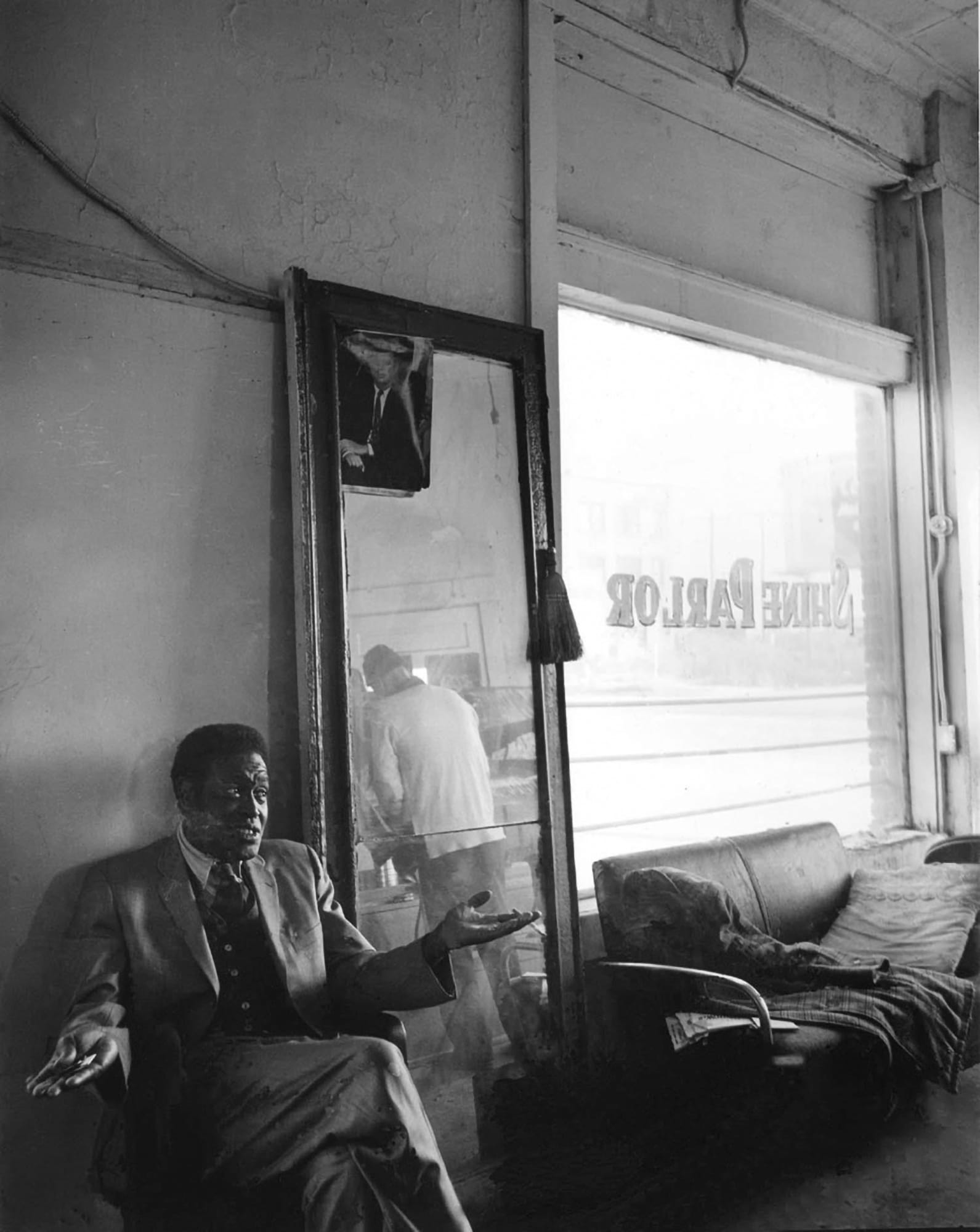

LEFT: “Shine Parlour II,” Tulsa, 1970 By Don Thompson - Photo by ©Don Thompson, Courtesy The Hulett Collection. RIGHT: Thompson stands with an image he captured in Tulsa, 1970 entitled “Baltimore Barbershop.” - Photo by Michael Kinney

“I still have that photograph,” Thompson says. “I made copies of it. Sometimes when I go to some of these lectures, I show the photograph: ‘This is my photograph that was taken over 50 or 60 years ago.’”

Despite the stress of the ordeal, the experience left a mark on Thompson. When he got out of the army, he took a correspondence course in photography for the next two years and started doing commercial photography. Using everything from Leica to Nikon cameras, he focused on weddings, class reunions and portraits.

“I was never really satisfied with that type of thing. I just didn’t like the commercial side of it,” he says. “I wanted to really get into something that I had been really interested in, doing some photographs that Henri Cartier-Bresson, Gordon Parks and other photographers were doing. I felt that I had a calling in my life to document injustice. I wanted to document what I was seeing: the injustice, the racism, the bigotry, the discrimination.”

Other projects Thompson has worked on include a photographic exhibit titled “Black Settlers, In Search of the Promised Land.” The portraits and stories of the men and women who escaped the 1921 Tulsa Massacre are on display at the Oklahoma State University-Tulsa campus.

The list of Thompson’s accomplishments, exhibits and honors he has amassed over the past half century would take up an entire page by itself. Black and white prints of Thompson’s work were recently added to the Hulett Collection in Tulsa. Photographs such as “Baltimore Barbershop,” “Shine Parlour II,” “Endangered Species” and “Three Against the Wall” are now part of the same collection as his photography idols Cartier-Bresson and Parks.

Yet when Thompson looks back on the day he captured the fall of Greenwood, he still feels contrite.

“To this day, my one regret is that I was not in the area fast enough because the bulldozers were faster than I was,” Thompson recalls. “I couldn’t get in that area quick enough because I worked at night. And the only time I could get into the area was during the daytime. I had pictured those areas that I wanted to photograph, and by the time I got into the area, they were gone. So, the very few photographs that I was able to capture, I was grateful for. I could have taken more, but the bulldozers were faster than I was.”