In April, one of Tulsa’s own returned to her roots to work on an important project. Many will know Judy Woodruff from her years anchoring and serving as managing editor for “PBS NewsHour,” a post she left in December. Today, she’s working on a couple of deep-dive projects, one of which is no small task: an exploration of America’s current state of divisiveness called “Judy Woodruff Presents: America at a Crossroads.”

“After I moved on from anchoring, the most important reporting I thought I could be involved in would be trying to understand where the country is right now, since we’re so divided. So much of what I’m interested in is looking at the heart of the country … it doesn’t get, in my view, covered by the press as much as the coasts,” Woodruff says. “What better place to start than where I was born? I do have family there. I’ve gone back a lot over the years … I have a sense of Oklahoma.” She’s quick with a disclaimer, though, assuring that while her connection to Oklahoma is strong, she makes no pretense of being an expert on our uniquely complex state or its equally complex people. And when she says this, she sounds very Oklahoman.

Woodruff has also launched a series of reports on disability issues. She and her husband, the columnist Al Hunt, have three children, Jeffrey (42), Benjamin (37) and Lauren (34). Jeffrey was born with a mild case of spina bifida and hydrocephalus. Woodruff told his story to the NIH Record, a publication of the National Institutes of Health, and in her advocacy has shared it often. As a child, Jeffrey was a smart, active boy who did well in school and loved to swim and ski, until, at the age of 16 he underwent a routine surgery that left him unable to walk. His vision, memory and speech were also impaired. “He was never to be the same person, except on the inside,” Woodruff told the NIH. “Jeffrey was still the social being he’d always been … but he now required a lot of help to get through the day.”

Woodruff and her husband absorbed the shock as best they could and set about helping Jeffrey, who understood what had happened to him but didn’t dwell. He graduated from high school and community college and then completed a four-year program at a school for students with physical disabilities. He now lives in a group home in Maryland, where he receives round-the-clock support.

Ever humble, Woodruff says, “I don’t want to claim to be something that I’m not. I’m first and foremost a journalist, but as the as the mother of someone with disabilities, I’ve tried to do whatever I could in any small way to support not just our son, but everyone with disabilities.

“I can’t pretend to understand what it means to be to be in a situation where you can’t go where everyone else can go, where you’re not looked at the same way, you’re not listened to the same way, you’re not treated with the same respect, you’re not included in the same way once you have one disability, much less several. And so I’ve wanted to do anything I could to raise the visibility of people with disabilities; to make sure that people think about them as people. They’re not just an interest group or people to feel sorry for.”

Both reporting series will be aired on PBS.

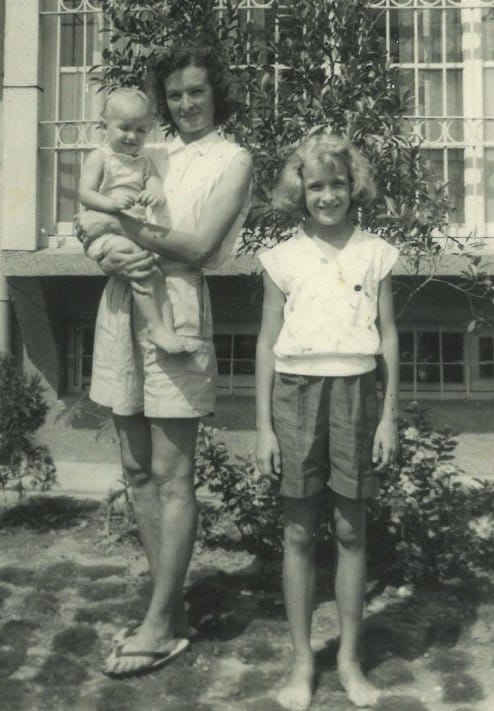

LEFT: Woodruff as a young girl in Tulsa / RIGHT: Woodruff with her mother and sister in Vietnam

Judy Carline Woodruff was born in Tulsa in 1946. She was named Judy after Judy Garland and Carline after her mother’s father Carl. Her own father, William, was a chief warrant officer in the Army; her mother, the former Anna Lee Payne, raised Judy and her sister Anita in full “Army brat” style, as the family moved from Oklahoma to Germany, then Missouri, New Jersey, Taiwan, North Carolina and finally landing in Georgia, near Augusta, when her dad was stationed at Fort Gordon. When Woodruff was in fourth grade, Anna Lee and her girls moved back to Tulsa for a six-month stint in 1956, while her dad continued his post in Asia.

Woodruff remembers traveling with her mother by ship to Mannheim, Germany, to reunite with her father who was stationed there. She was four when they began the journey. “The reason I know this very clearly is because I had my fifth birthday on the ship going to Germany. I have a clear memory of that party.”

Though she and her family traveled the world, Oklahoma never really left the picture for Woodruff, or for her mother. They returned frequently over the years to visit family there and in Oklahoma City. “I was born in Tulsa. My mother is buried in Tulsa.”

Even after spending years in Georgia, Anna Lee called Tulsa home. In the end, Tulsa returned the favor. “She died in 2013. But she always told me she wanted to make Tulsa her final resting place,” says Woodruff. “And so I made sure that that happened after she passed.” Like too many women of her generation, Anna Lee wasn’t able to finish her education, leaving school at 14 to care for her siblings after her father died. Woodruff’s maternal grandmother, Anna Lee’s mother, worked three jobs to support her five children.

That was not the future Anna Lee wanted for her own daughters. “She always said to me when I was growing up, ‘You have to get an education. Diapers and dishes can wait.’ I didn’t so much appreciate it at the time. I thought she was just lecturing me. But I’ve recognized that was the best possible advice I could have had, and I owe her so much.”

High school in Augusta, Georgia, was followed by a two of years at Meredith College in Raleigh, North Carolina. She studied math until a professor encouraged her interest in political science. After transferring to Duke University in 1966, she became active in campus student government and interned during two summers for Georgia Representative Robert Grier Stephens, Jr. Woodruff, a pragmatist, noticed how women in Washington, D.C., were treated at the time, and switched her focus to journalism.

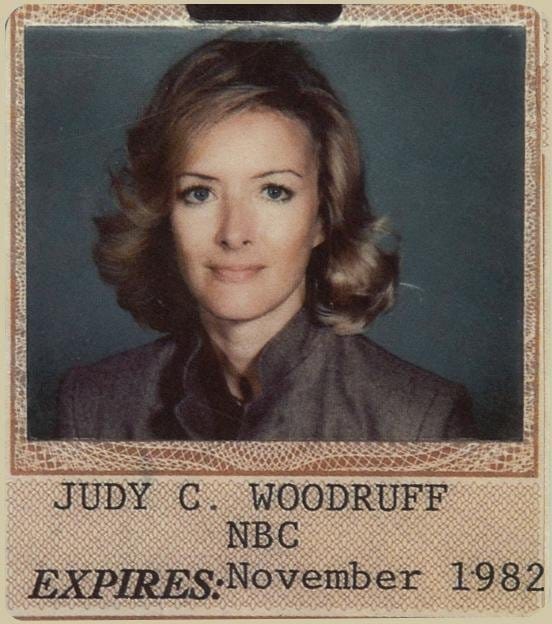

Her first job “in journalism” was working as a secretary in the news department of an Atlanta television station, where she also presented the weather on Sundays. Next came a reporter job with another network affiliate, covering the Georgia Legislature and anchoring the noon and evening news. Soon enough she was covering 10 Southeast states and the Caribbean for NBC, during which time she was assigned to cover President Jimmy Carter’s 1976 campaign.

In 1977 she moved to Washington, D.C., to become a White House correspondent for “NBC News,” and chief Washington correspondent for the “Today Show.” From 1983 to 1993, she spent a decade at PBS, working on “Frontline with Judy Woodruff” and as the chief Washington correspondent for the “MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour.” During that time, she covered presidential conventions and moderated the infamous vice-presidential debate between United States Senators Lloyd Bentson (D-TX) and Dan Quayle (R-IN).

CNN came next, with Woodruff co-anchoring “Inside Politics” and “The World Today.” While at CNN, she co-anchored coverage of some of the biggest news events of the time, including presidential campaigns and elections, the Oklahoma City Bombing, the Centennial Olympic Park Bombing and 9/11. Before returning to PBS in 2006, she taught journalism at Harvard University and Duke, and hosted a monthly program, “Conversations with Judy Woodruff.” Back at PBS, Woodruff made history for (among other accomplishments) co-anchoring the “PBS NewsHour” with the late Gwen Ifill, the first time two women ever anchored a network news program.

LEFT: Woodruff on airplane with press, including Sam Donaldson / RIGHT: Woodruff in studio at PBS News

Her awards and accolades are too numerous to list. She has achieved and covered more in American journalism than almost anyone else, but for Woodruff journalism isn’t about any of that rigmarole. Journalism is a crucial pillar of American democracy.

“I was taught from the very beginning journalism is supposed to be just the facts. You go out, and you report … And that’s what we do as journalists. Our job is to record and observe what’s going on and to share that with the public. We obviously do some editing in our work; we pick and choose what we leave in and what we leave out. But our job is to faithfully reflect what’s going on in the world,” she says.

It’s a responsibility she does not take lightly. “I have a pretty fundamental view, which is it’s the foundation of our democracy. It’s one of the foundations that when the founders themselves decided what was going to be in the Constitution and in the Bill of Rights, you know, freedom of the press was right out there with the other important freedoms, from religion to assembly, speech and so on. We are one of the pillars of our democracy … it doesn’t get any more fundamental than that.” •