It was a coincidence that director Loren Waters started shooting Tiger on the day Dana Tiger returned to silk-screening T-shirts at her art gallery after three decades.

“It was, like, just totally serendipitous, total destiny that we were there with the camera, and I had no idea that’s what she was going to be doing that day,” Waters recalls.

Of course, at the time, Waters also didn’t know she was shooting what would become Tiger, a short documentary about a family of globally influential Native artists, or that this story would get into Sundance and SXSW in 2025. What she had was a nice camera package gathering dust between jobs, a knack for storytelling and an instinct that she was in the right place.

“I think of Loren coming into my life as a result of the prayers that I do make,” says Muscogee painter Dana Tiger, the point-of-view figure and beating heart of Waters’ almost 13-minute film about the Tiger family. “It’s like a fairy tale, considering how it all came about.”

The First Chapter

Waters, a Norman native and University of Oklahoma graduate, has worked in film since 2019, starting at the Cherokee Nation Film Office. As a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe, she has been captivated by using film as a medium to share Indigenous stories for years.

Her career quickly expanded to working in production for Apple and Netflix, with Sterlin Harjo’s Hulu comedy series “Reservation Dogs” being her big break. She rose through the ranks to become the show’s background talent casting director, and that’s how she met Dana Tiger.

“I think Sterlin actually sent me her number because he wanted her very particularly for this [role],” says Waters. “We just clicked instantly.”

After deepening their friendship on and off the set, Waters asked to record the Tiger family stories on her iPhone. The more she heard about the Tiger legacy, the more she knew she was witnessing something special — and that it needed to be shared.

Independently from “Reservation Dogs” and her film gigs, Waters had begun to work on personal documentary projects. First was Restoring Néške'emāne in 2021, about the environmentally hazardous site of a former Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian boarding school shut down by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Next was ᏗᏂᏠᎯ ᎤᏪᏯ (Meet Me at the Creek) in 2024 about the attempted restoration of the Tar Creek Superfund site in Miami, Oklahoma. Falling into the themes of Indigenous communities, love and loss she had shot before, Waters asked if the Tiger family could be her next documentary subject; Dana Tiger agreed.

“So I called Dana, and I was like, ‘Hey, what do you think about me coming out to film with you?’ I had heard some of her story and had recorded some of it on my phone, and was blown away by the things that [she] and her sister and her family had been through,” says Waters.

One day one of shooting, Waters showed up at the family’s house with no initial plan. Seeing Tiger silk-screen shirts with her son helped her focus the narrative.

“And then, from there, the story really started to sink in. Like, ‘Oh, wow.’ This is a huge deal for the Native community that they’re bringing [silk-screening t-shirts] back. Those shirts have been in “Reservation Dogs,” several movies now, around since the ’80s.”

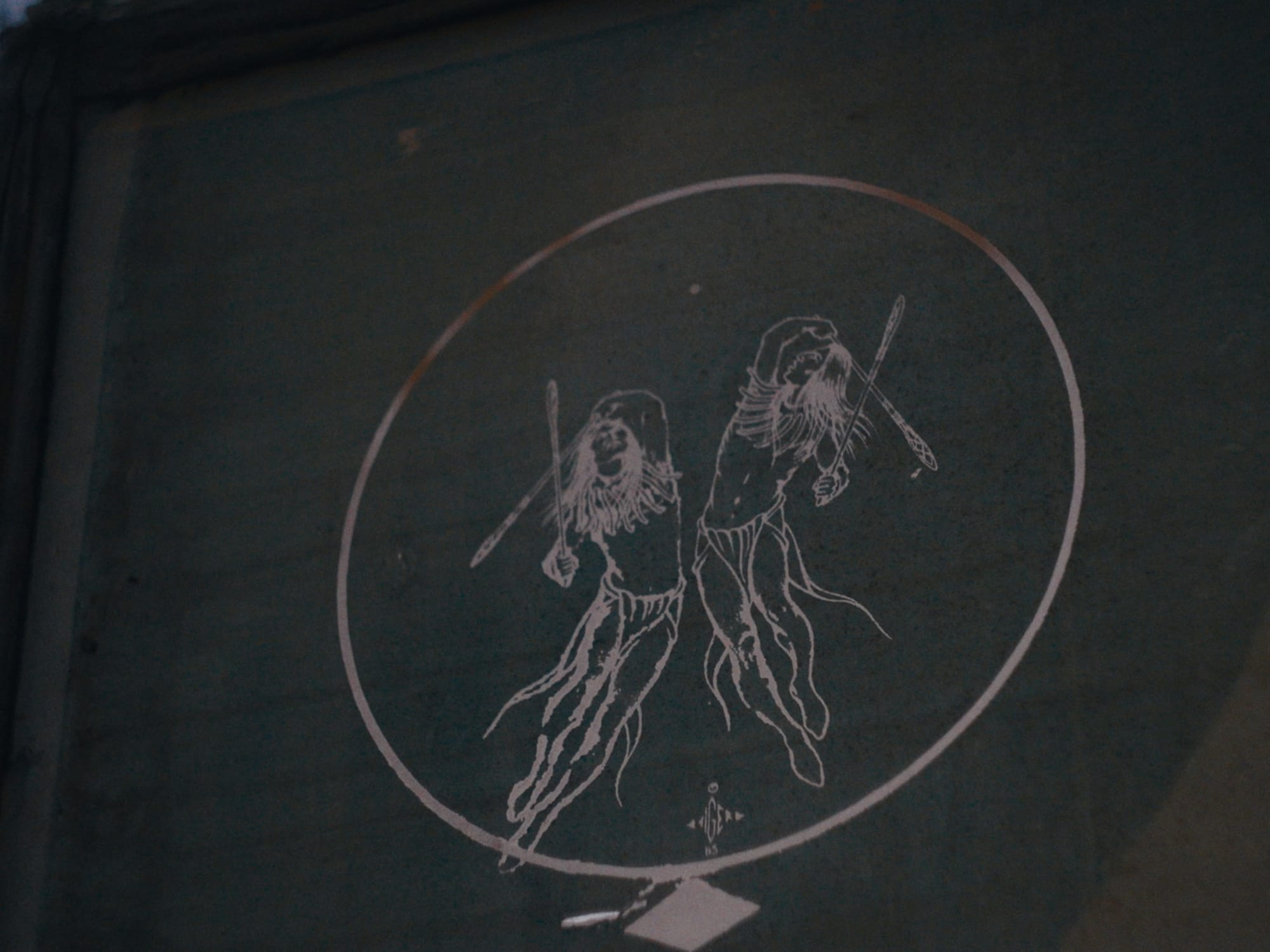

Dana Tiger painting on glass as seen in Tiger / One of many of the Tigers’ unique shirt designs featuring stickball players / Original Tiger tee silk screen used in the 1980s

Tiger Power

The arts run in the Tiger family’s blood: Dana Tiger is the eldest daughter of Jerome Tiger, a prolific Muscogee Creek-Seminole painter from Tahlequah. Some critics laude Jerome as the “Rembrandt of American Indian art.” Jerome’s children (Dana, Lisa and Chris) became artists as they grew older, as did Lisa’s children Christie and Lisan.

The arts also were a source of healing for the family: After Dana’s father died tragically young at 26, Dana’s mother, Peggy Richmond Tiger, began to create and sell prints of Jerome’s work — which was as challenging as it was fulfilling.

“When she started the Jerome Tiger Art Company after dad’s death, so the world would know what a genius he was, she had these beautifully done prints,” remembers Dana. She said her mother Peggy and her mother’s cousin Molly would try to sell the prints, but weren’t having much success. After being told by a Texas businessman that Peggy and Molly were “fighting a big battle with a short stick” and that they should let a big publishing company handle the print sales for them, Peggy wouldn’t back down.

“Mom said, ‘Okay, I’ll pretend to be the secretary. You’re going to be a saleswoman. Mr. M.A. Babcock, the fictitious owner, is going to be in the back, too busy to talk to anybody.’ Mom would answer the phone. ‘I can help you.’ ‘I want to talk to the owner.’ ‘No, I can help you with anything. He’s busy right now,”’ says Dana. The plan worked, and print sales skyrocketed.

“And so after several years, she wrote or called that guy, and she said, ‘Now I’ve got a big stick,’” says Dana with a smile.

Working in art sales prepared the family for the next stage: the founding of the Tiger Art Gallery.

In the early 1980s, Peggy Tiger and Dana’s uncle Johnny Moore Tiger Jr. founded the gallery to sell silk-screened shirts featuring his work. His captivating prints, when silk-screened on shirts, quickly grabbed the public consciousness beyond Native art enthusiasts. The art on the shirts also expanded to incorporate the rest of the family’s paintings and work.

As Dana states in Tiger while lying on a pool diving board, “I’m talking 24 hours a day, in that gallery, silk-screening shirts to fill the orders with JC Penney and all over the world.”

But after the death of her brother Chris at 22, the Tiger Art Gallery and the entire operation were put on pause. The family went their separate ways for a time, and the silk-screening area of the gallery gathered dust and trickled into disrepair.

In the meantime, Dana flourished with her own powerful artistic career, being inducted into the Oklahoma Women’s Hall of Fame in 2001. Her art, which centers on strong Native women, has been shown in local exhibitions in Tulsa and global exhibitions in Paris.

“I painted what I saw all women were. But I didn’t feel it myself, but I knew the world, the world could.”

Where the Heart Is

The Tiger family home, where they still reside, is a museum of their family’s artistic legacy. Art from every generation hangs on the walls, and Chris’ pickup truck is parked in the driveway. Waters and Director of Photography Robert L. Hunter chose to capture this setting and Dana’s story in a way far from traditional.

Waters blended newly digitized 8mm and 16mm family footage that Dana and her sister Lisa hadn’t been able to see before, archival photography and newsreels with a gossamer, floaty and experimental approach to shooting Dana and her family in their home. Matching this creative approach with the spirits of the artists who lived there, Waters chose to interview Dana in unusual locations and with non-traditional framing. After not having a plan for day one, each subsequent day required storyboarding.

“I was like, ‘OK, how can we showcase Dana’s art in a beautiful way that’s not just filming it on the wall? How can we do an interesting interview of her?’ Maybe I was like, ‘Dana, how do you feel about doing an interview on the diving board of your swimming pool? And she’s like, ‘That’s great. I do that all the time; I go out there and talk to the fish,’” says Waters. “So it ended up being something that I felt like was truly Dana in that way.”

“I’m the quirkiest, weirdest person on the planet, and I don’t know, you know, nothing phases me like that. I never, ever get embarrassed, really,” adds Tiger.

A whisper of Tiger’s voice pervades the film’s sound design, saying the names of family members and the titles of the art that was printed on the shirts. The rest of the soundtrack incorporates a song from artist Wotko Long, “Estmvn Estomen Fullastskis,” (which is about two sisters separated from each other on the Trail of Tears), contrasted with the garage rock song “Soft Stud” by Black Belt Eagle Scout (one of Dana’s favorites). This is all cohesively blended with an original score by Trevor Kowalski.

The final assembly of the film by editors Amanda Moy and Eva Dubovoy feels personal and intimate but not voyeuristic. As Tiger is the only person who speaks during the film’s entire runtime, audiences will feel they’re sharing the space with her, hearing these tender moments directly from the person who experienced them.

“It’s just, it’s overpowering. I just feel it throughout my whole body because it’s, you know, it’s living our lives now, but it’s carrying and caressing and holding what all happened before,” says Tiger.

“I’m sitting in Uncle’s room. I’m looking over here where they were filming, but the spirit of my uncle and my dad, my brother, all are here in this house.”

“It’s up to me to see the world doesn’t forget what they did.” –Dana Tiger in Tiger (2025)

Dana Tiger with Chris Tiger’s truck as seen in Tiger

The Roar of the Crowd

After the picture was locked and it was time to send it off to film festivals, Waters knew this film was special — and the programmers of some of the most renowned film festivals in the country agreed. Sundance received 11,000 short film submissions for the 2025 festival, which took place Jan. 23-Feb. 2. Only 57 short films were accepted, Tiger being one of them.

“So those numbers are wild to me,” explains Waters. “We were chosen out of 11,000; that’s crazy. But at the same time, I also knew how special this story was, and I really believed in it, and I believed in the work that my collaborators did to help bring this to life.”

Waters’ belief in her and her team’s work led her to rent an Airbnb for Sundance a couple of months before they knew they got into the festival — “for safety,” she notes. After her Sundance acceptance, she started a GoFundMe on behalf of the Tiger family’s non-profit, the Legacy Cultural Learning Community, so the entire family and crew could attend the world premiere. The campaign was fully funded by mid-January.

Additional high-profile acceptances soon followed the Sundance announcement, like music, art and tech festival SXSW, which takes place March 7-15 in Austin, Texas. Adding more evidence that Waters is on the right track with her career, Forbes inducted her into the 2025 class of 30 Under 30. Unsurprisingly, Tiger and Waters deeply respect and admire each other, especially each other’s art.

“When I look back on when I first met Dana and saw some of her paintings, I was so drawn to

her art, and that was the first time that I had realized, like, ‘Oh, that painting looks like me,’” says Waters. “‘She Means Business’ is one of her paintings that I love. I’m like, ‘I want to be like that woman in that painting.’”

A story that started as sharing the power of the Tiger family legacy has expanded to include a young Native woman whose own star is growing brighter.

“I just feel empowered and I just feel my children and Loren and all these filmmakers, their empowerment just spread through all of them, you know, the whole community,” says Tiger. “My mother would be so damn happy.”

To learn about the short documentary Tiger, visit tigerfilm.co or follow the film on Instagram @tigerteefilm. You can also keep up with Waters and Tiger on Instagram @lorenkwaters and @danatigerart.