Chef Loretta Barrett Oden has spent most of her professional life introducing diners to the foods of the First Americans. The Shawnee native and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation grew up surrounded by Native women — mother, grandmother, great grandmother, aunts and great aunts — who taught her how to forage and cook the traditional foods of the tribe, along with its lore. Cooking was a social event; the kitchen a campfire where stories were shared.

“I was very fortunate to be surrounded by so many strong women,” Oden says. “Having great grandmothers, great aunties, all the way down to me meant that I was able to learn how to prepare those pre-Contact dishes and hear the stories of my people and family. We’ve always been an oral people, and we’re losing our elders — and as we do that, we’re losing our stories.”

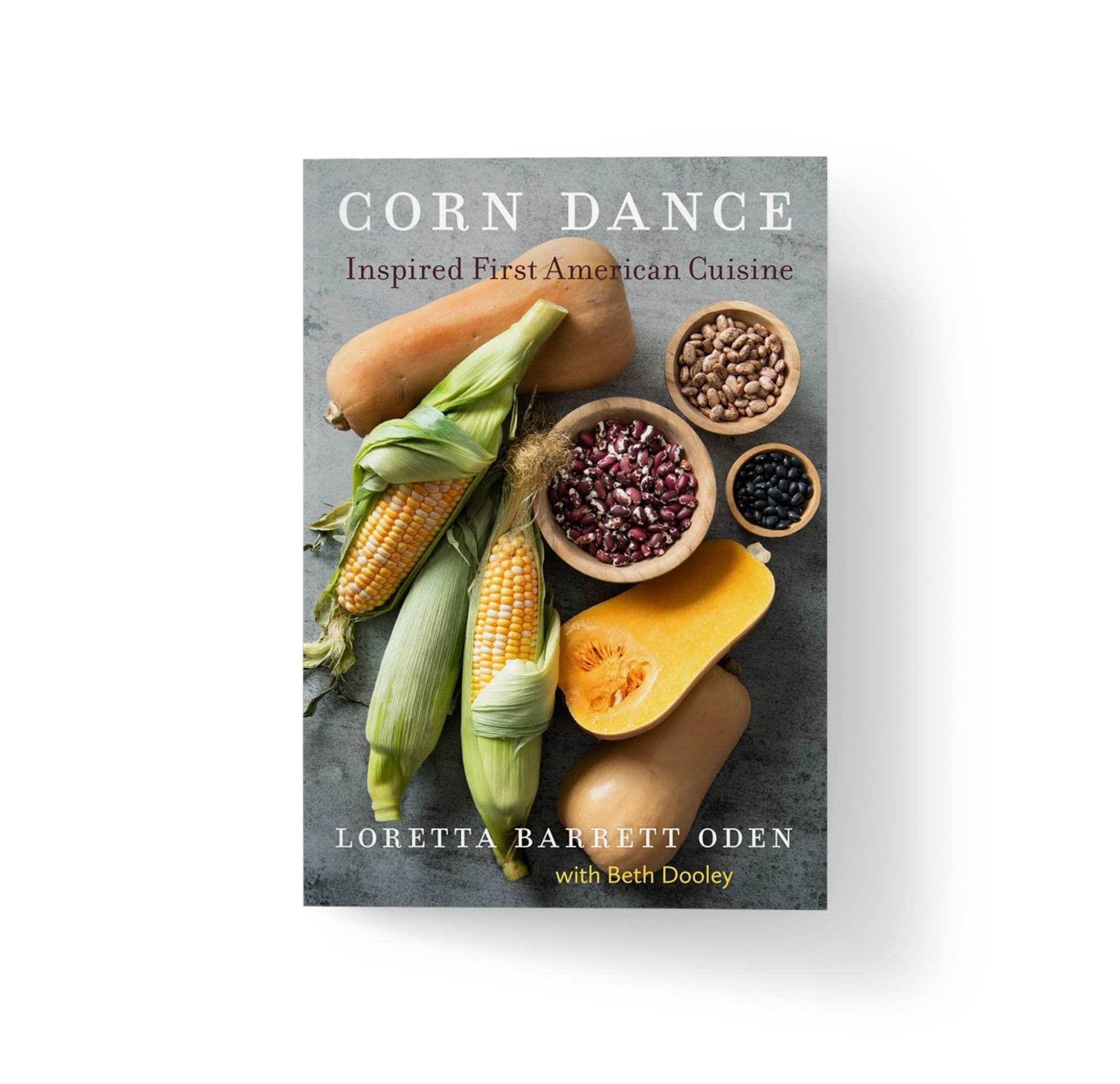

To help stem the losses, she’s written Corn Dance: Inspired First American Cuisine, published by the University of Oklahoma Press. The book is a collection of First American recipes and culinary wisdom, blended with stories from Oden’s personal life and professional career. It’s aimed at home cooks, not chefs, but Oden includes her nearly seven decades of experience in the chef world in techniques and pro tips. (She turns 81 before this issue goes to print.)

“Native cooks had all the cooking techniques we’re familiar with except deep fat frying,” Oden says. “There was just no big iron kettle to put all that bear fat in. Rendering fat did go on, and things were packed in batches, but mainly we’re plant-based with very small portions of meat. And of course, the agrarian tribes grew the Three Sisters: corn, squash and beans.”

Tribal differences make it difficult to talk about Native American cuisine as a monolithic genre — much as regional differences make Italian and Chinese food far more complex than Olive Garden and P.F. Chang’s would lead casual diners to believe. That difficulty is present in Oden’s role as culinary director for the First Americans Museum: How do you accurately represent 39 individual tribes, most of which were here due to forced relocation?

“One of the first things I had to push back against in representing so many tribes was fry bread,” Oden says. “It exists because of removal; it was never a traditional staple. As a kid we got the commodity packs from what we called The Agency, much like many Oklahomans got commodities in boxes each month. It was not the best food, so we made do. In Oklahoma, fry bread and Indian tacos are prevalent. The powwow circuit helped spread fry bread and Indian tacos. I felt compelled to push back against that because of the health issues in Indian country: diabetes, gluten intolerance, lactose intolerance, etc.”

Foraging is central to traditional Native dishes. Dandelion, sunchoke, poke salad, lamb’s quarters (an amaranth relative) and more wild, foraged plants end up in the dishes, so where you are matters. Some tribes, including Oden’s, make tea from corn silk and pine needles. They were originally medicinal, of course, but they can be enjoyed for the flavor, much like Italy’s amari liqueurs, which were also originally designed to be curative.

The analog to Italian is helpful here. A major reason Olive Garden thrives is because Americans believe they’re getting Italian food. In fact, we were raised to believe that it’s quintessential Italian: heavy pasta dishes, red sauces, breadsticks, all with tons of cheese and salad, of course. The actual cuisine of Italy is regional and seasonal. Olive Garden and its doppelgangers are offering an Americanized version based on pop culture and generic simulacra of “Italian food.” Native American cuisine has the same problem on a smaller scale. Ask someone what constitutes Native American food, and the most common response is likely to be Indian tacos, which certainly function as a symbol of Native ingenuity and determination — you have to eat to live and you can only eat what is available — but are not, strictly speaking, pre-Columbian Native cuisine.

“Native cuisine is very diverse, and it’s regional and seasonal,” Oden says. “You have salmon in the Northwest, chiles in the Southwest, Three Sisters everywhere, chocolate, berries, pineapple, papaya, potatoes, tortillas, buffalo, all kinds of fish, even dragonfruit. Translating it to non-Native diners should be easy because 80% of the foods enjoyed around the world today had their origins in America. They left here and came back as Irish potatoes, Belgian chocolates, etc., so our ingredient base should be familiar to everyone.”

To facilitate the writing — Oden calls herself a “not a disciplined thinker” — OU Press hand-picked James Beard Award-winning writer Beth Dooley, who previously co-wrote well-known Minneapolis and Native American Sean Sherman’s The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen, to help with the project.

“Corn Dance includes a lot of my life stories, with recipes designed for the home cook, so I used audio files, and then Beth worked on it. I went to Minneapolis, where she makes me get out of bed, and then says, ‘Now talk,’” Oden says with a laugh. “The audio files have helped, but so have my composition books. I take notes and jot things down constantly. I have hundreds of composition books, so when I croak there will be a treasure trove of my more lucid thoughts.”

The book is set to debut Oct. 3, but to tide us over, the influences behind Oden’s food — the kind of food she served at her Corn Dance Cafe in Santa Fe many years ago — can be experienced at Thirty Nine, the restaurant at the First Americans Museum, 659 American Indian Blvd. in OKC.

“One of the great ironies of my life is that I got into food because I hate politics,” she says. “I thought cooking could help me make my way in the world, but nothing is more political than food: sourcing, access, sovereignty, preparation, etc. All human beings have it in common. Through the book, I hope that my story and these dishes will heighten people’s awareness of who we are as Native Americans, remind them that we’re still here and bring them together for conversations.” •