Michael Hulett never imagined himself back in Tulsa, working as an art dealer and running his own gallery—but as so many great stories do, his career in art started with a love affair.

“In my 20s, I dated a girl that was super into photography. I picked up a camera and fell in love with photography, and out of love with her, and that’s where my photo career began.”

As they say, the rest is history. Twenty years later, Hulett is a full-fledged art dealer, and a fanatical collector. After serving as the director of the world-renowned Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica, curating exhibitions across the U.S. as well as in London and Paris, Hulett and his wife returned home to Tulsa to be closer to family. Opening a gallery wasn’t yet in focus, but Hulett’s massive personal photo collection was growing larger by the month, and in desperate need of new space.

“Honestly, I was racking my brain about what I was going to do here in Tulsa,” Hulett recalls. “I thought I might work at Philbrook, or find a job at a gallery. One day, I was boohooing about this to my wife, Hannah. She said, ‘You have 25,000 photos in boxes. Why don’t you open a gallery and start selling those ’til you run out?’”

Two years later, Hulett still hasn’t run out of photos, and has successfully carved out a market of Tulsans who appreciate them as much as he does. Today he’s the owner and curatorial eye behind The Hulett Collection, a small, impressively chic photo gallery on the west edge of Cherry Street featuring works by legends of the medium. At any given moment, the walls are filled with rare photography from artists like Ansel Adams, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Elliott Erwitt and Hulett’s own artistic icon, Louis Stettner. (As it happens, Hulett’s is the only gallery in the Western Hemisphere showing Stettner’s work, making the collection’s presence in Tulsa all the more impressive).

© LOUIS STETTNER / COURTESY THE HULETT COLLECTION

With the exception of Ansel Adams’ landscapes, Hulett’s gallery primarily features figurative, humanist works depicting everyday subjects caught in poignant, beautifully mundane moments.

“It’s a lot of anonymous women, fleeting moments in time,” Hulett says. “Nowadays it’s usually kids. I have three kids of my own now, and I’m experiencing in real time … the awe the world holds for them. I immediately connect to that when I see it in a photo.”

That awe is embodied perhaps no better than in Hulett’s favorite piece from his latest show: a silver gelatin print of a child staring up the meteoric mayhem of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, captured by Stettner circa 1974. It hangs tucked away in the back of the gallery—an enduring reminder of the same awe and nostalgia that drew Hulett to photography in the first place.

In many ways, Hulett’s curation integrates old and new, bringing iconic moments throughout history into current context. In addition to late greats like Stettner and Adams, Hulett has widened his curatorial aperture to include works from contemporary artists, too.

“Part of what I’m trying to figure out is how to make classic photography appeal to American audiences,” he says, “especially Americans in their 30s and 40s, who typically prioritize experiences over tangible assets.”

It’s not just an aesthetic choice, but a strategic one. Art collecting has primarily been accessible to buyers with disposable income and discerning taste—both of which typically come with age. But growing appreciation for the artform requires growing the customer base, too, and contemporary artists offer an entry point for young, nascent collectors.

© JANE HILTON / COURTESY THE LITTLE BLACK GALLERY

“For me, it’s ‘How do I turn owning a piece of history or fine art into an experience itself, so that it’s not just an investment you’re making, but something you interact with on a daily basis?’ I’m still figuring that out as time goes on,” he says.

It invites the question: What exactly makes the old feel new again? Of course, there’s the old adage of seeing something in a new light, which the gallery does beautifully. But the pieces in the collection are all united by an important throughline: their potential for autobiographical viewing.

Whether depicting a streetscape, the shadowed symmetry of skyscrapers or the taut line of a mother and child tugging each other in different directions, the photos in the collection have a way of pulling the viewer in and placing them in the center of their tension. As time and context cast new shadows on the photographer’s original intent, even frozen moments can feel like present reality. In this way, these photos aren’t just relics of history, but living mirrors, where snapshots of time stir new understanding in the viewer’s own experience even decades later.

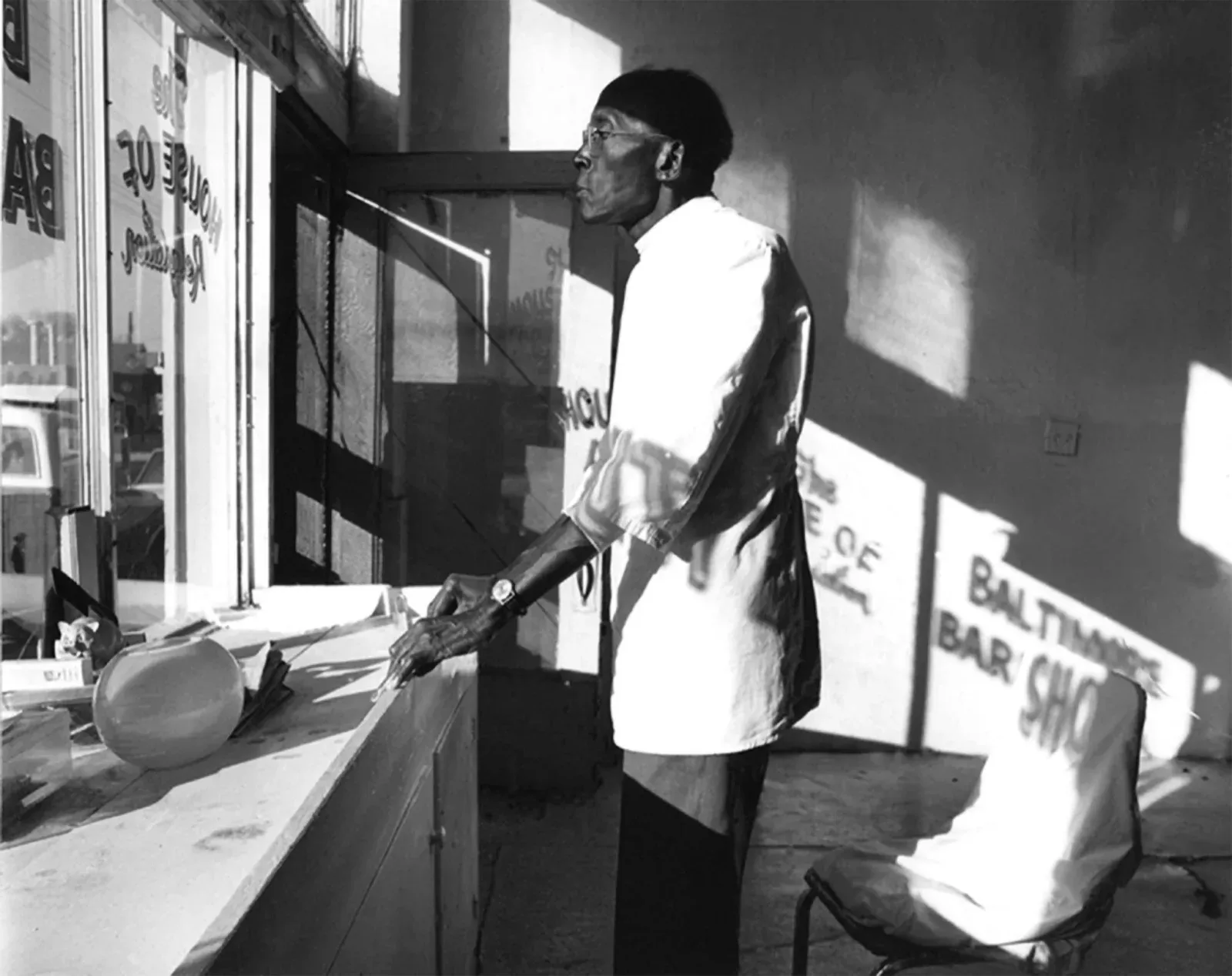

LEFT: “Baltimore Barbershop,” Tulsa, OK, 1970 By Don Thompson. RIGHT: “Portrait of Michael Hulett” 2024, By Kit Young

The Hullet Collection feels right at home in a city experiencing its own cultural renewal, and this too is by design. Hulett wanted the gallery to be additive, offering Tulsans and visitors access to historically significant works not typically found in this corner of the world.

“In my head, I asked, ‘What can I bring to Tulsa that won’t be seen here otherwise?’ I knew there were a lot of galleries supporting local artists and photographers, but I didn’t see anyone bringing national or global artists to Tulsa at the scale I’m trying to do here. And that’s not to say an artist from Finland is inherently better than an artist from Tulsa. I just don’t think that exposure would’ve happened otherwise.”

The Hulett gallery will center Tulsa’s own history and talent soon enough with an upcoming show featuring Tulsa-born photographer and social justice documenter, Don Thompson.

“He’s the real deal,” Hulett insists of Thompson, whose work has been featured in iconic venues like the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “But his street photography, documentary and portraits have never really been shown properly.” Hullet hopes to do Thompson’s work justice with an online and physical exhibition of Thompson’s work capturing the Greenwood District in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s—images that feel classic and captivating even 50 years later.

Ahead of that, Hulett is hosting an exhibition with contemporary artist Jane Hilton, a UK-born photographer documenting the evolving cultural landscape of the American West, on view now through Nov. 15. The evocative “Cowboys and Drag Queens” exhibition reinterprets old and new icons of the West through portraits of cowboys in full color, and Reno drag queens in black and white. Hulett describes the show as a way to blend two seemingly disparate sides of a cultural spectrum, bringing both into new conversation with one another, expanding our understanding of what the colorful region can mean.

As is always the case, the images on view will be available for purchase—but we shouldn’t be surprised if a few find a permanent home in Hulett’s personal collection. After all, he’s a collector first, and a dealer second.

“I sell prints so I can buy prints. That’s the cycle,” he explains, characterizing dealing as something of a hack he’s found to feed his own constant craving for new pieces.

“A lot of dealers just represent artists—the work comes in, the show ends and the work leaves. But I worked for a gallerist who also obsessively collected, and that’s how I caught the bug. I’m not in this just to sell art,” he insists. “I’m in it because I’m passionate about collecting it, too.

“And so the cycle continues.”