Take heed: You’ve only got until April to experience Kiarostami: Beyond the Frame. The Oklahoma City Museum of Art’s multimedia retrospective exhibition of artworks and films by Abbas Kiarostami, the widely acclaimed Iranian photographer, filmmaker and visual artist, is ambitious, comprehensive and stunning — and you’re going to want to go more than once.

No other museum in the world has assembled such a comprehensive show of the late artist’s thought-provoking yet playful work. The only exhibition that comes close was mounted in 2021 (after being delayed due to the pandemic) at Centre Pompidou in Paris, according to Kiarostami’s son, Ahmad Kiarostami, who also serves as the president of the non-profit, San Francisco-based Kiarostami Foundation. He spoke with Luxiere candidly about growing up with an internationally acclaimed artist for a father, and about how his relationship with his father’s work has evolved.

“Everybody in my family is an artist,” says Ahmad; “I’m the only one who’s not. I was rebellious by not becoming an artist. My job is in technology that I have had different startups. When I was a kid, I decided I didn’t want to follow my father’s path or to be under his shadow.” He laughs. “Look at me, I’m 50 and I’m sitting here talking about my dad. So … the sensitivity of a teenager is not there anymore.” He’s modest, though. Like his father, Ahmad is prolific: He’s produced documentaries, founded tech startups here and abroad, made music videos and launched a remarkable platform, Docunight, which allows its subscribers to stream Iranian documentary films — there are currently hundreds in its library. The son of a documentarian brought these hundreds of documentaries to global audiences, including those mesmerizing films made by his father.

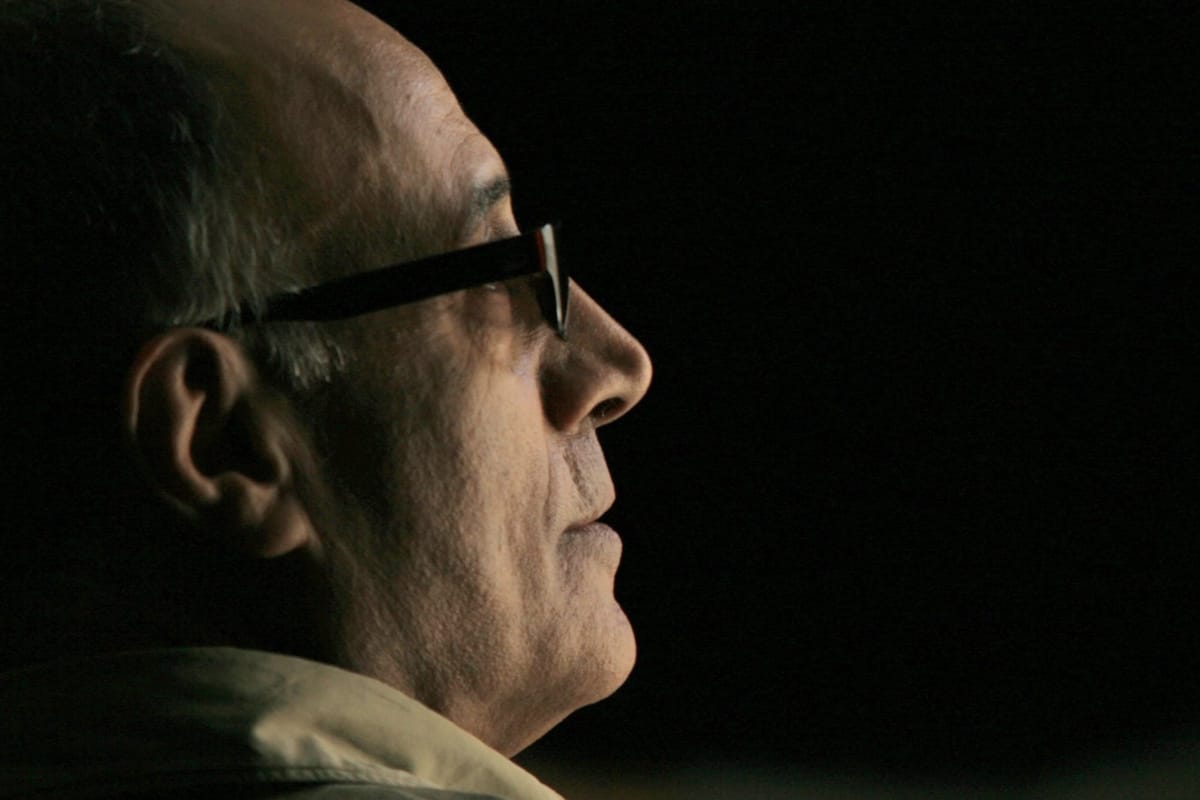

It turns out that Michael J. Anderson, president and CEO of the OKC Museum of Art (OKCMOA), has long been fascinated by Abbas Kiarostami’s work. His interest was borne out of Kiarostami’s stature as a film director.

“When I was really starting my studies in film, right around the year 1999 or 2000, he was perhaps the most important figure in the global art cinema,” Anderson remembers. “And so, when I was really starting to get interested in films outside of the United States, trying to figure out what was happening around the world, his name repeatedly came up … My first publication in film was about his films, I think back in 2004. I’ve written other things on his work.”

In a remarkably 21st-century move, Anderson contacted Ahmad through social media. “I actually just messaged Ahmad Kiarostami on Twitter and asked him if he’d be interested in doing an exhibition in Oklahoma. And he responded pretty quickly that he was.”

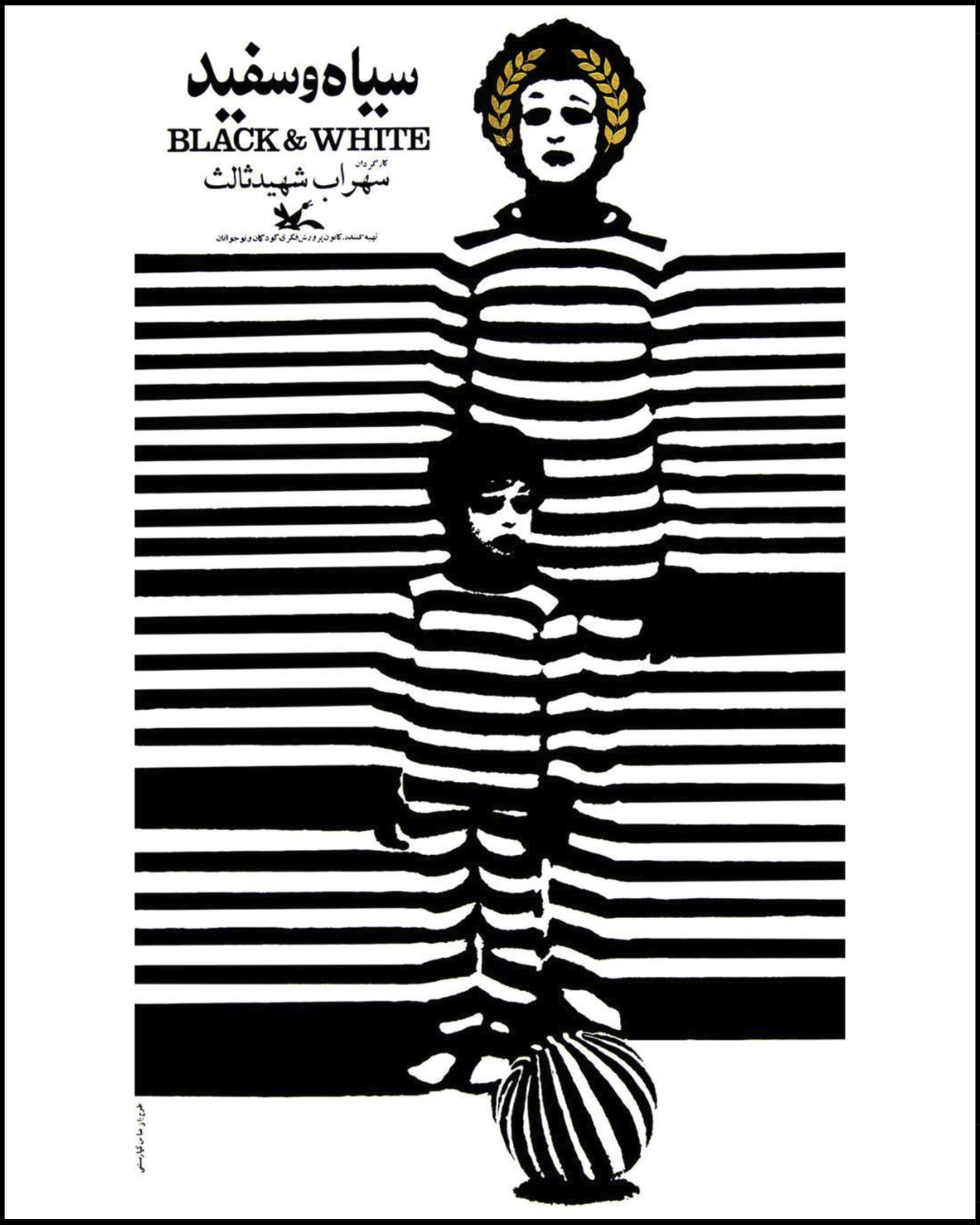

The exhibition, the first American museum offering since the artist’s 2016 death, occupies the entire third floor of the museum. From Kiarostami’s early children’s films and graphic design work to his immersive large-scale photographs and installations of his 21st-century video art, it’s all here. This exhibition features the world premiere of the complete “Regardez-moi” portfolio, Kiarostami’s series of photographs depicting visitors to the Louvre and other museums.

While the exhibition, like Kiarostami himself, is not overtly political, Ahmad allows that giving voice to Iranian arts and artists — specifically in times like these — is, if not an act of defiance, at the very least a rejection of the narrative that Iran is just one thing. Yes, it’s a deeply divided country and yes, a boiling point has been reached between the regime and the people. But it’s also a beautiful, ever-changing place. It’s also just an ordinary place filled with people living regular lives. Mundane and beautiful, like everyplace else.

Ahmad continues, “Unfortunately, the regime doesn’t understand … and they have left no space for people, and no way out. And I think it’s a very dangerous situation right now … So I think they’re going to fight until the very last moment … At the same time, people have no place to go, either. There’s a book called The Art of War, an old Chinese book, by Sun Tzu. He taught to always leave an escape path for your, for your enemy, otherwise they must stay and fight until the last moment, the last drop of the blood. The situation now is both parties have no nowhere to go. And I think this is a very dangerous situation. But I think that’s the only way, the only path moving forward. Unfortunately.”

Some of Kiarostami’s works have never been seen in Iran. Images from the “Regardez-moi” series, the final part of the viewers’ experience at OKCMOA, are of people (mostly at the Louvre) caught in the act of looking at works of art. There’s a cheekiness to this series; visitors will note playful visual motifs and similarities between the works being viewed and the viewers themselves. But because some of those works being viewed are classical paintings depicting the nude form, audiences in the artist’s home country may never see these images.

Bringing Iranian voices of all kinds to light is part of the mission of Docunight, as well. “At the start of the uprising in Iran in 2009, I caught myself having a lot of opinions without really knowing what was going on in Iran. Because I left Iran eight years prior to that. And I thought, ‘What’s the best way to educate myself about what’s going on in Iran?’ And when I say what’s going on, I don’t talk about specific topic, I mean in general, and Iran is a very young, fast country. Probably that’s not the image that people have from outside, but things change pretty quick … So I thought, how can I learn about that? I thought news is not a good idea, because they only talk about very specific things … So I thought the best way is documentaries. And I started watching more documentaries from Iran, myself.”

Yes, friends, Kiarostami: Beyond the Frame is a must-see exhibition for a multitude of reasons. Significant. But especially, says Anderson, because “It’s not a dutiful exhibition in the sense that you’re not going to just check it off your list. It’s not cultural vegetables. There’s something immersive and magical about the experience of these works. And it’s really because of that that they’ve become these iconic works of contemporary art.”