When he walks into Shades of Brown, the coffee shop in his Brookside neighborhood, the baristas greet him by name. He used to play in a metal band. His parents were professional magicians. He’s taking singing lessons and wants to learn to act. He’s looking at getting a Harley.

He’s also the newest principal dancer at Tulsa Ballet.

Around here, you don’t necessarily expect to see a ballet dancer with a French accent casually chatting over a coffee shop counter. But Aubin Le Marchand, originally from Paris, is no stranger to getting right into the mix of things, wherever he is.

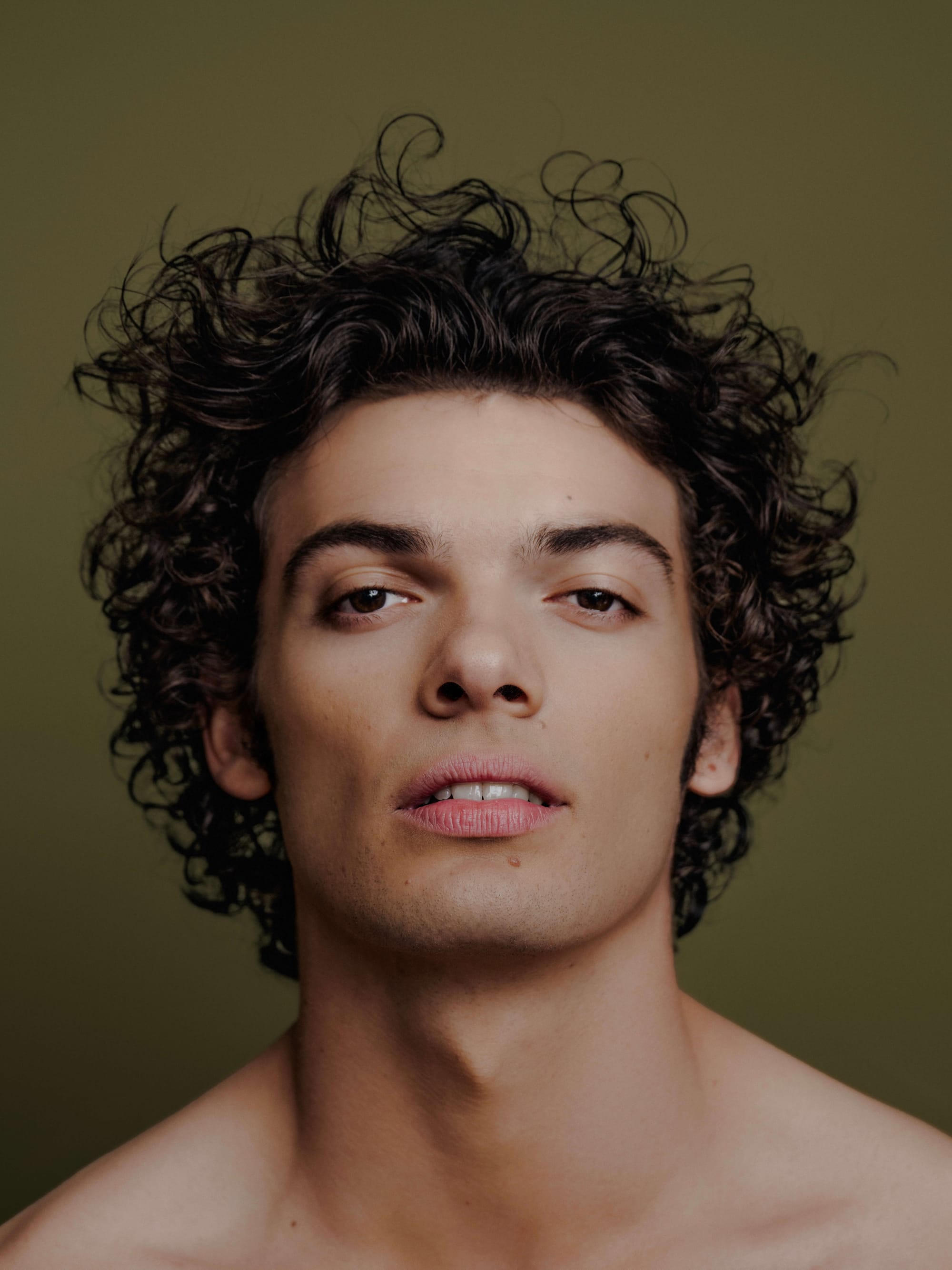

The 24-year-old arrived in Tulsa last summer just after the Father’s Day storm. On stage and in person, you might say he brings his own kind of weather system with him. With a crown of dark curls, wide brown eyes and a rakish smile, Le Marchand is tall for a dancer—or maybe it’s just the size of his personality that makes him seem a bit larger than life.

You’ll see that in action if you make your way to a Tulsa Ballet performance this season (visit tulsaballet.org for a schedule and tickets). Le Marchand’s dancing is dramatic, athletic, finely detailed and bursting with energy, honed in the centuries-old tradition of the Paris Opera Ballet school and full of the voracious passion of a young man at the start of his career. Starting next month, he’ll take the stage for his second season here after dazzling audiences last year as a soloist in works like Romeo & Juliet, Don Quixote and Celestial Bodies.

“I have a big dream,” he says. “I have big dreams in general.” When Tulsa Ballet’s Marcello Angelini offered him a job after an audition in London, following two years dancing in Croatia, Le Marchand seized the opportunity to move to the U.S. “He asked me, ‘What do you want?’ I said, ‘I want to be a star.’ Maybe you know the French basketball player Tony Parker? He said, if you expose your dream to someone and the person doesn’t laugh at you, it’s not big enough.”

No matter the size of the dream, bringing on a new leading dancer is serious business at Tulsa Ballet. But Le Marchand fits the bill. “Aubin is tall, handsome, a great partner and a versatile dancer,” Angelini says. “He has been a great acquisition for the company.”

A Life on Stage

Le Marchand got his first taste of the stage around age 6, joining his father in magic acts (even, at one point, riding a unicycle) and putting on house shows of his own. He started ballet and trumpet lessons when he was 7, and entered the prestigious Paris Opera Ballet school two years later. For several years in his teens, after an injury, he started to shift away from dancing (“I was growing my hair and playing guitar in the hallways; a soft troublemaker”), eventually quitting the school altogether.

But it wasn’t long before he returned to training, realizing that while he could play music at any age, dancing at the highest level has a far shorter shelf life. Post-graduation and barely out of his teens, with theaters closed due to the pandemic, he linked up with a dancer in the north of France whose parents had a dance school. They spent the next year training together and organizing outdoor terrace performances that included dance, paintings and sculpture—plus the magic he’d learned as a kid—and earning money by literally passing a hat at those shows before finding the job in Croatia.

“You can’t ask people to be like everybody and expect extraordinary.” –Aubin Le Marchand

The range of ballets Le Marchand performed there prepared him well for the mix of classical and contemporary works he’s encountering in Tulsa. “The repertoire is great [here]. The level of the company is very high. It’s very unexpected for a town like Tulsa,” he says. One quibble? “I wish we danced more. When we’re a dancer, we tend to forget the final destination: It’s the stage. That’s our business, not the ballet studio. I’m a bit extreme in my way of seeing things, but when we finish one production, until I reach the next one, I forget the feeling of being on stage. You have to renew it.”

Le Marchand’s eyes light up whenever he talks about any kind of performing, especially when it involves a mix of disciplines, something unexpected, or an example of radical commitment—such as French singer Jacques Brel getting on a plane to sing in one city and then flying to another for a second show on the same day. “This inspires me. This motivates me,” he says. “This way, I find life beautiful.”

He’s finding the beauty in Tulsa at restaurants like Oren, Doc’s and Mondo’s (“for a French person, you have high expectations for food”) as well as places like Philbrook. He and his girlfriend have stopped in Oklahoma City, Dallas and Paris, Texas, during her visits to the States, and they even made their way to Durant for a rodeo—although “she came with white sandals. We didn’t get the dress code,” he says.

“Many people say there’s nothing going on here, but if you know where to go, or if you want to, you can find it’s really nice,” he continues. “The hospitality here is not like in big cities, I think. It’s not like this in Paris.” And he’s found his perfect weekend spot for hanging out with beers and cigars: “I wonder how much money I left in one season just at Churchill’s.”

This coming season, Le Marchand is especially excited to work with choreographer Kenneth Tindall on a new Alice in Wonderland, and to grab as many opportunities as he can to nourish his multifaceted creative life, bringing that richness back to his dancing. He’s as hungry for experiences on the ground as he is on the stage, and his enthusiastic presence in the everyday life of Tulsa makes him an unconventional ambassador for his art—one who’s equally comfortable dancing at the bar (where he’s not shy about letting local music-lovers know when the next Tulsa Ballet performance is) and at the barre.

“Do you know ‘Inspector Derrick’?” he asks. “It was a German TV series, very bad. It was always on after lunch, for old people to nap. One famous French actor said, ‘If we remove all the crazy people, I am afraid we will end up with only “Inspector Derrick.”’ You can’t ask people to be like everybody and expect extraordinary.” •