Anthony Barboza, Helen Levitt, Tseng Kwong Chi, Diane Arbus, William Eggleston.

Unless you are steeped deeply in the world of street photography or art, these names may mean nothing to you. However, it was their work that documented the 1970s and ushered in a new era of photography by challenging society’s notions of what art is and who can shoot it.

These are just a few of the artists whose work was recently on display for six months at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., part of the exhibit The ’70s Lens: Reimagining Documentary Photography.

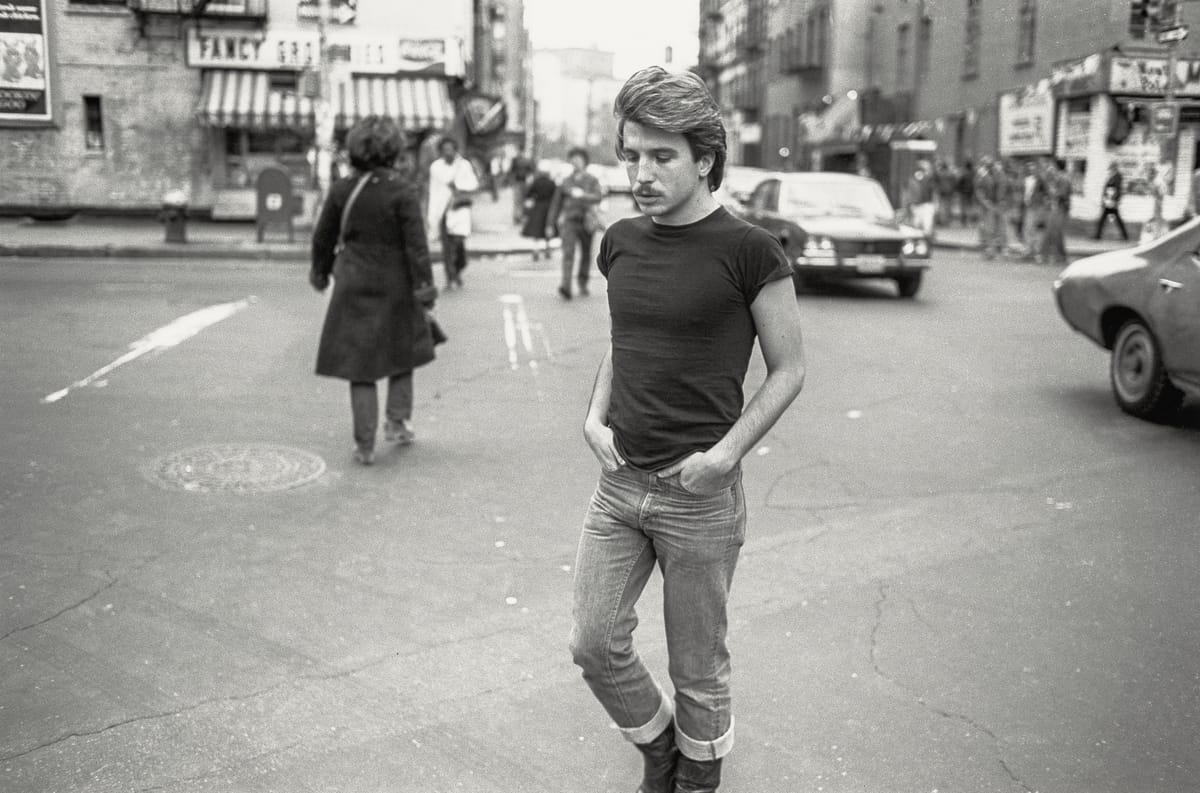

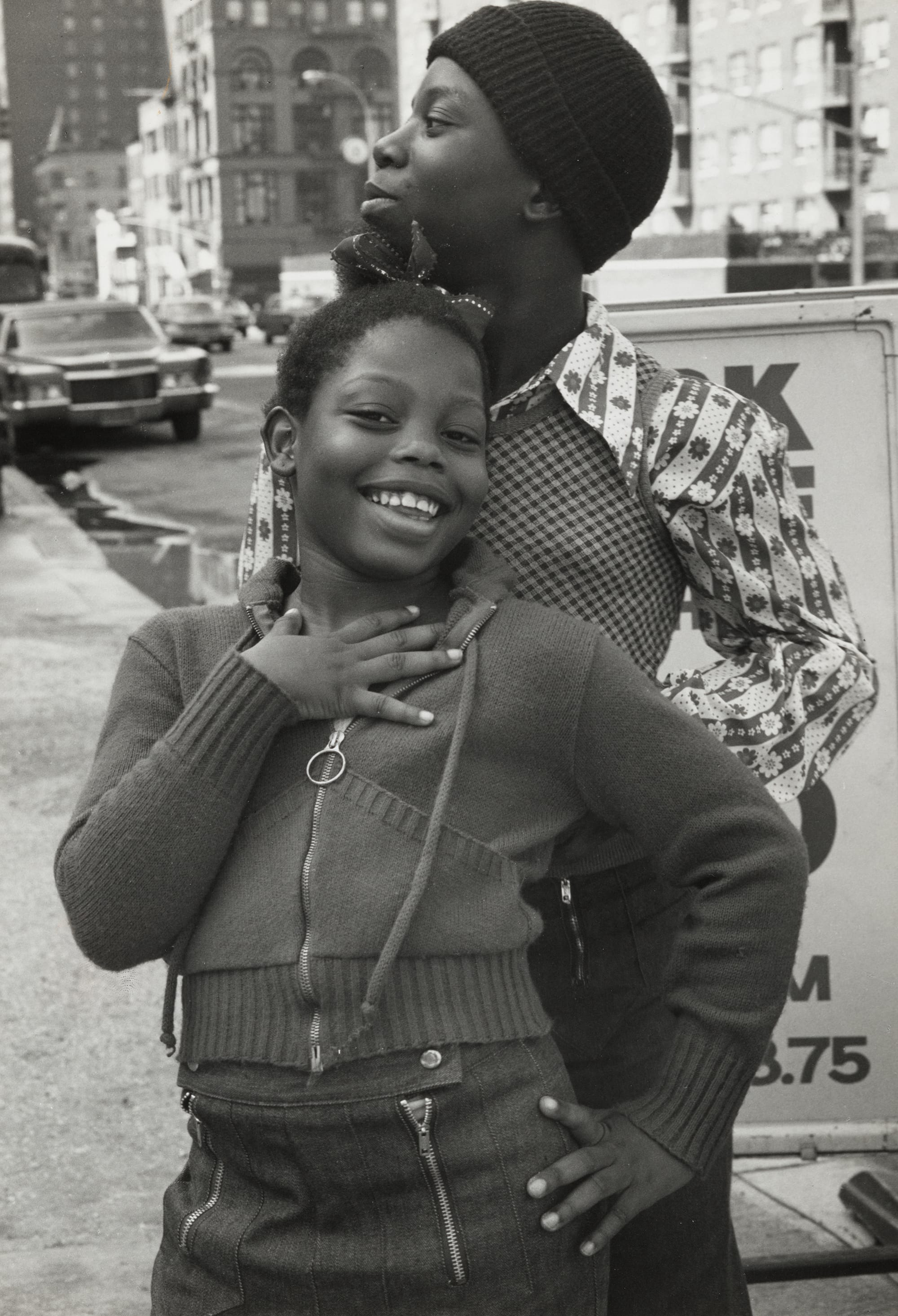

LEFT: Anthony Barboza New York City, 1970s gelatin silver print - National Gallery of Art, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund. RIGHT: Helen Levitt New York, 1972 dye imbibition print - National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund © Film Documents LLC, courtesy Zander Galerie, Cologne

“The profound upheaval in American life during the 1970s inspired artists to question the objective nature of documentary photography,” Kaywin Feldman, director of the National Gallery, stated at the exhibit’s opening. “The extraordinary photographs on view in this exhibition explore their diverse and compelling responses, revealing relevant connections to today’s thinking about community and who gets to represent it, as well as broader concepts including photographic truth, equity and environmental responsibility.”

According to Andrea Nelson, associate curator in the department of photographs at the NGA, the idea was born out of an interest in performance photography that was happening in the ’70s. That slowly transformed into a broader documentary style that was taking place at the time.

“The ’70s is an interesting moment in the history of photography, particularly in the history of photography as it sort of intersects with the art world and wanting to be taken as a very serious art form,” Nelson says. “It’s one of the pivotal moments, I think, in the history of photography where you see that, you see that growth or you see that change that’s happening.”

According to Nelson, you can’t talk about the 1970s without first taking stock of what took place during the 1960s. It was a decade full of turbulence, wars, protests, riots, assassinations and political upheaval. For many, it may have seemed like America was going to boil over and something new was going to come from it.

But that didn’t happen. That left many young men and women searching for answers.

“In many ways, it’s like coming out of that time questioning and what happens after all of that questioning,” says Nelson. “What was interesting is that you really have maybe more of the fulfillment of that questioning and critique that was happening in the ’60s. I don’t think you would have this kind of questioning of what is documentary or who gets to be a photographer if you didn’t have that unrest that was kind of happening in the ’60s. It comes out of that moment of questioning.”

If photography in the ’60s was about documenting the struggles of society in a straightforward, hard news manner, the ’70s reflected a search for truth in a time of uncertainty. Americans witnessed soaring inflation and the Watergate scandal, as well as protests about the Vietnam War, women’s rights, gay liberation and the environment.

“I think what’s so interesting with photography is it is in some ways a more accessible medium and you have more people engaging with it, and it kind of expresses what’s happening at the time,” says Nelson.

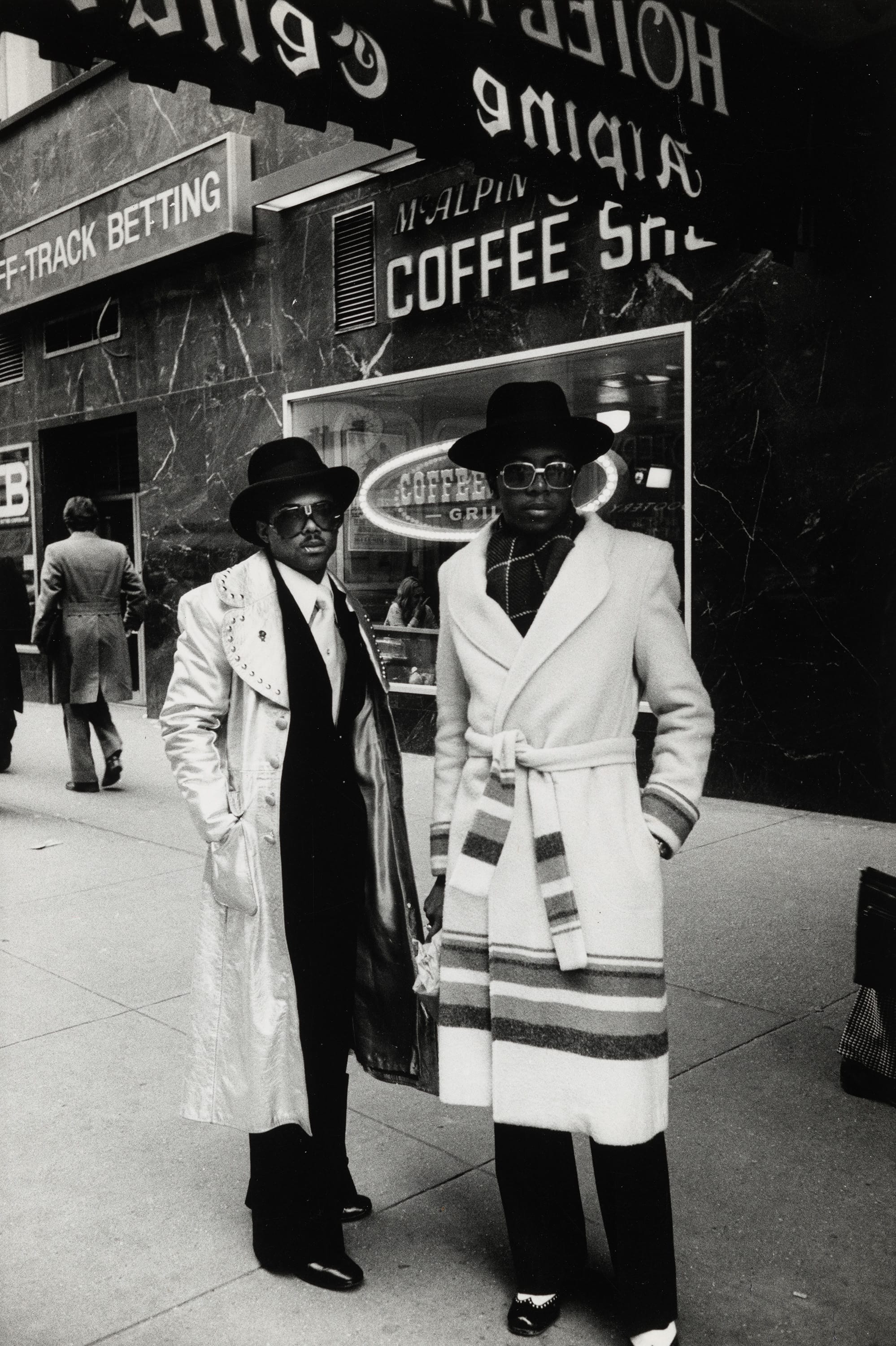

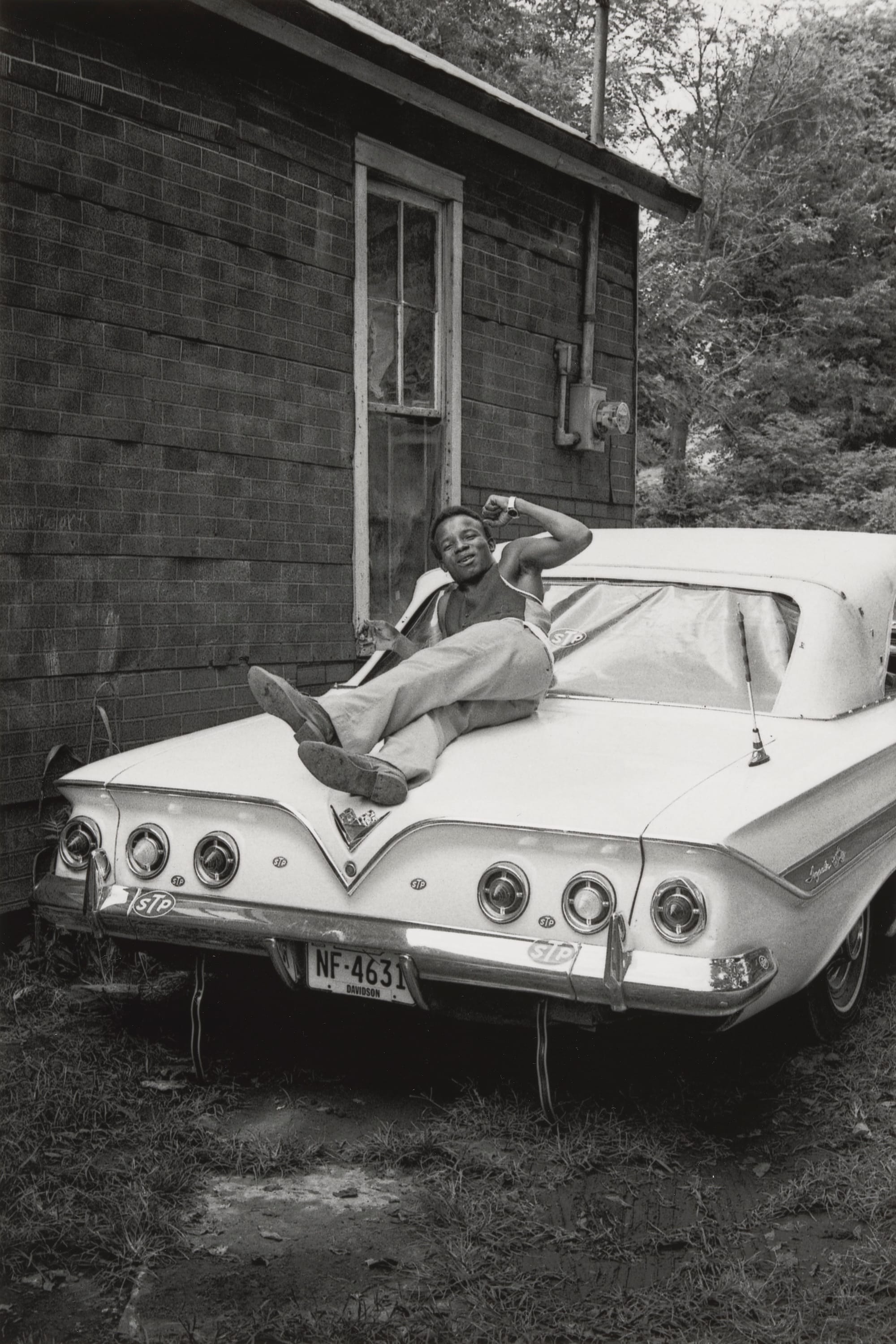

LEFT: John Simmons, Will on Chevy, Nashville, Tennessee, 1971, printed 2024 - National Gallery of Art, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund. RIGHT: Anthony Barboza, New York City, 1970s gelatin silver print - National Gallery of Art, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

She took on the task of going through the National Gallery’s permanent collection to find pieces that fit the exhibit’s various themes: Seeing Community, Experimental Forms, Conceptual Documents, Performance and the Camera, Life in Color, Alternative Landscapes and Intimate Documentary. Then came the difficult job of whittling her options to a manageable 147 photographs from 86 artists. All but two photos came directly out of the NGA collection.

“I went through hundreds and hundreds just looking at what we had and picking,” Nelson said. “You always have to make hard choices because you don’t have an unlimited amount of space. There were definitely photographers that weren’t quite fitting the theme that I had to let go.”

Several artists featured in the exhibit have produced iconic photography books that have become valuable collector’s items today. But when they were honing their crafts in the 1970s, that didn’t appear to be their focus.

“Photography has become an art form; when I started, it wasn’t. It’s about producing an image,” Barboza recently told The New Bedford Light. “When you take a camera and look at the world, there are a lot of things out there that you could photograph or not. You have to make that decision. It’s the same as any other art form. There is no difference between any of the art forms to me. It’s all how you feel and how you think and what you see.”

When The ’70s Lens shut down on April 6, the photographs went back into the gallery’s archive. But Nelson hopes those who ventured to D.C. to see the exhibit left with a better understanding of what was taking place during a unique moment in history that is still shaping how we see the world today.

“What I did hope people would take from it is to see what an amazing array of photography was really being produced through this questioning of what is documentary,” she says. “That questioning of that practice, and expanding it, just really opened the field to so many different viewpoints and different practitioners. To see such a rich variety of practice that was happening at the same moment.”