Something has to be across the street from the Louvre. You can’t have an entire town of nothing but Fallingwaters and Taliesin Houses or they’d lose their impact. And a building can be genuinely admirable as a work of craft without also having to be a work of capital-a Art.

But while not every project can be, or should aspire to be, an unparalleled, inimitable icon of design, the opposite extreme — spaces with meager inspiration, with little care in construction, with paltry ambition (beyond, perhaps, size) — is disappointingly common, even at higher price points where bigger does not necessarily mean better construction.

How does a builder strike the balance between creative aspiration and functional utility? Austin Tunnell, founder and principal of OKC firm Building Culture, draws inspiration from the examples of the past, with a focus on long-lasting durability.

“We’re a small design/build company that is focused on building things that can last centuries rather than decades,” says Tunnell. Contemporary Americans, he says, “kind of live in a disposable culture, and our building culture reflects that; our buildings today are meant to last 30-75 years. We’re looking to build on the architectural innovation of centuries called structural masonry. All the oldest buildings in the world are built of some form of structural masonry, whether it’s the Pyramids, or the Pantheon, all of Europe that was rebuilt during the Renaissance — they rebuilt it out of structural masonry. There are buildings still standing today that have centuries more left in them. And so we’re taking that concept: Let’s blend the best of old and new to come up with beautiful, lasting, durable architecture that enriches everything around it.”

Basically, that means solid, load-bearing walls — very few two-by-fours and no wooden frames like you typically see in houses under construction, quite a lot of bricks. Like, a lot of bricks.

“In one of our Wheeler builds that’s a 2,000-square-foot house, there are 90,000 bricks in it. The walls are 16 inches thick,” he says.

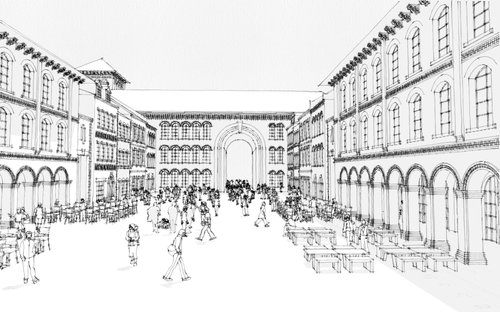

Talk to Tunnell for any length of time and you’re likely to hear the term “vernacular,” and not referring to linguistics. He explains, “In the traditional sense, vernacular was just the local architecture of the place. If you lived in a place with lots of trees, you would build out of wood; if there was lots of rain because you lived in the tropics, you would have big eaves to keep the rain off, versus the adobe in New Mexico. So really buildings tailored to the environment. Also, it kind of has a humble nature to it. These aren’t the civic buildings, or the biggest, grandest, greatest buildings, just … the normal stuff that people are building that accomplishes what they need it to accomplish. That’s kinda what we’re talking about; we’re not just trying to build great big civic buildings — although that would be very fun. Landmarks are great, but the way we think about it is most of the greatest cities and towns and neighborhoods in the world, they’re built 99% just common vernacular and 1% punctuation, the cathedrals and the libraries and the civic buildings. Really, cities are mosaics, and 99% of them are simple but beautiful pieces that fit together, and together those buildings make a larger impact than just an individual building by itself.”

Deliberately focusing on projects that are less likely to make a name for yourself might be an unusual approach, but Tunnell had an unconventional path to this vocation — in fact, he started his career as a CPA, but that quickly grew stale. After a year and a half, he joined the Peace Corps — “trying to kind of find meaning in life,” he puts it – and while in Panama, he met a master mason who introduced him to the tenets of urbanism: “this idea that how we build shapes how we live.” After a childhood in the suburbs of Houston, where reaching any destination outside the house was time-consuming if not practically impossible without a parent to drive him, the concept of a denser, more accessible environment really struck a chord.

“That is my life’s mission, I feel,” he says. “And it’s not that the suburbs shouldn’t exist, there should absolutely be suburbs, it’s just that you can’t have the majority be suburbs. It’s not the way to house the majority of people. And really all our suburbs are highly subsidized by taxpayers for infrastructure and all that — miles of highway and sewer line — and per capita, it’s so ghastly higher in suburbia than it is in relatively dense but comfortable urbanism. And it’s just an unsustainable practice on so many levels; whether it’s the health level, or climate change, or ecology, or economics, or community.”

The urbanist mindset should have some appeal in Oklahoma City, a metropolis that, to put it delicately, is not unfamiliar with the concept of suburban sprawl. After getting itself established and refining its practices by adding housing to the Lake Eufaula-adjacent planned community of Carlton Landing, Building Culture has begun building in the Wheeler District just south of Interstate 40, as well as some custom homes around the city. Tunnell also speaks highly of the work underway in Selah, a new urbanist development just south of Norman to which his firm is contributing some of the infrastructure. “It’s exciting to be in Oklahoma City. There’s a lot of energy here. My wife and I really enjoy it.”

While structural masonry is a time-tested concept, its comparative rareness in contemporary architecture has meant a little more difficulty for Tunnell and his team in explaining their concepts and sourcing their materials.

“We design everything,” he says. “So far, all of the buildings we’ve done I’ve designed myself, and then we build it ourselves and we do the interior design ourselves. It’s really intense, like writing a book; it happens over time and is a really intimate process. But my hope in the longer run is to move into development, once I get my design/build company really up and strong and have a really great sub base and have gotten all my materials and all that, to really move into infill development and building within our own development rather than doing one house here and one house there. So that way we’re really creating places around our buildings — not just the buildings themselves, but the space between the buildings.”

Tunnell is looking forward to making a lasting contribution to life, and the quality of life, in and around OKC. He’s just going to need a few more bricks.